Ads, Subscriptions, and the Missing Middle

Publishers need to make a living. Journalists, video producers, musicians, and bloggers all have to pay their bills.

The two common ways of making money from online content are:

- Free content with ads

- Subscription content without ads

Sometimes publishers use both, but with a reduced number of ads for subscribers, magazine-style.

The trouble with subscriptions is that people can quickly feel saturated. Once you subscribe to WaPo, NYTimes, WSJ, you might want to read that LATimes article, but don’t want to sign up for yet another monthly subscription. The commitment to pay a recurring fee is a big one.

On the other end of the commitment spectrum is the no-commitment world of ad-subsidized content.

The trouble with ads is that everyone hates them. In order to make the screen real estate more valuable, advertisers get really creative about tracking people. They track people to learn what ads they might engage with.

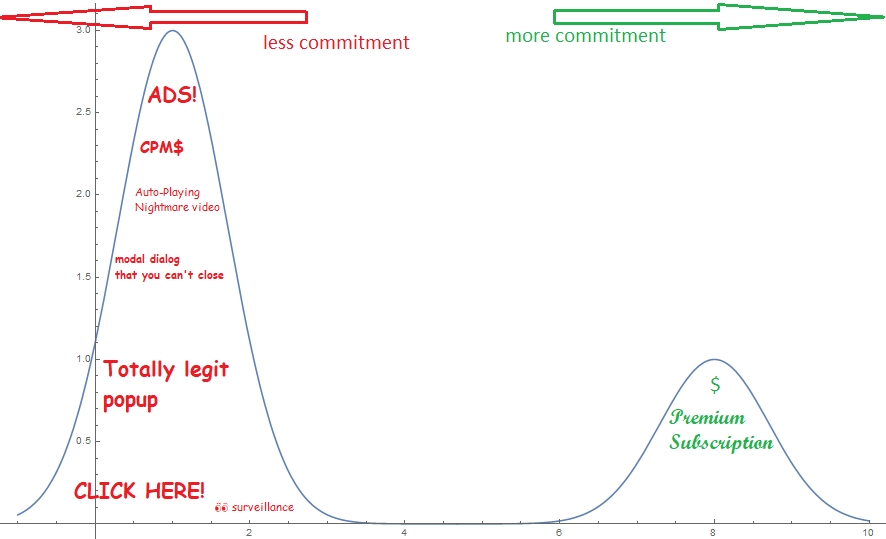

These two extremes are the dominant choices today in 2020, but I believe there is a viable third way.

The missing middle

Between the no-commitment and high-commitment extremes is a low-commitment middle. One where readers pay small amounts of money for individual articles. This is sometimes called micropayments, and many versions of this idea have been tried before. The big problem with micropayments using credit cards is that credit card transactions are expensive. This is why stores sometimes have minimum amounts that they will accept on a credit card. Credit card networks like Visa and MasterCard charge some percentage of the transaction cost plus a fixed fee. For example, 2.6% + 10¢. The reason this is bad for small payments should be obvious: if a blogger wanted to charge 1¢ per blog post, the reader would have to pay 11¢, and most of that would go to the financial intermediaries, not the blogger.

Prior attempts at micropayments

Here are a few attempts at micropayments, this list is not exhaustive, but it covers enough conceptual territory to be useful for this article.

- Flattr

- Brave browser and Basic Attention Token

- Bitcoin Lightning

- Ethereum state channels

Flattr solves the fixed priced problem by only sending out the payments on a monthly basis. The way it works is you put in a fixed recurring amount in your flattr account, let’s say $20. Every month, that $20 is divided up among all the things you Flattr-ed.

The biggest weaknesses of this approach is that it’s voluntary and requires an account. This isn’t a business model, it’s more of a charity scheme. It also requires a some up-front work by users to set up and fund a flattr account. Call this up-front work the bootstrapping problem.

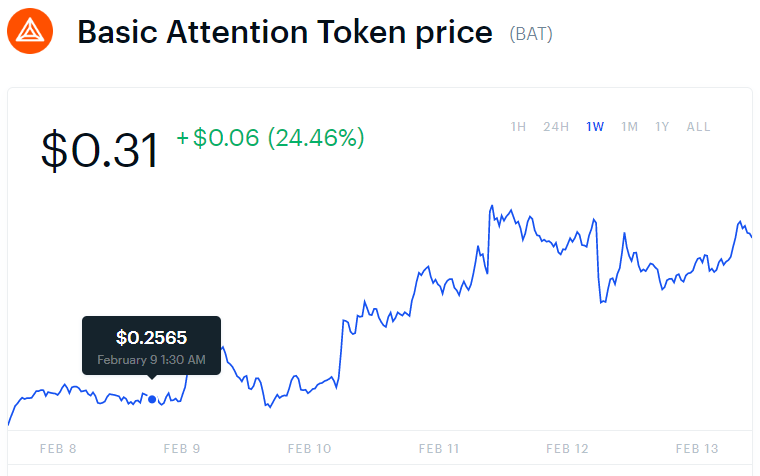

Brave and the Basic Attention Token are an interesting approach. The Brave browser is based on Chromium, and was developed by the inventor of JavaScript. By default, Brave blocks ads and trackers. It also comes with a native currency called BAT, for Basic Attention Token. Here is a recent chart of the BAT/USD exchange rate from Coinbase:

Brave let’s people opt-in to “privacy respecting ads” and then gives the users 70% of the ad revenue. Brave pays people to look at ads, and then that money goes into a browser wallet that can be disbursed to content creators automatically, in proportion to how long they are on each site. For example, if I had 100 BAT, and I spent 50% of my time on Wikipedia, 30% on the cats subreddit, and 20% of my time looking at London Tsai’s math art, then Brave would send out 50 BAT to Wikimedia Foundation, 30 BAT to Reddit, and 20 BAT to Mr. Tsai’s account. There is more to it, but this simple scenario gives a good feel for what Brave/BAT are all about.

Brave solved the original bootstrapping problem by using the existing ad ecosystem to get some cash into people’s wallets for easy micropayments. Of course, there is a new bootstrapping problem: getting people to install Brave and either opt-in to those ads, or directly funding their accounts instead. Also, those payments are in a non-standard cryptocurrency called BAT, whose value fluctuates quite a bit, so this all makes it more confusing for everyone.

As for the other two attempts: Bitcoin Lightning and Ethereum state channels, these are similar things, and they allow very small payments to be sent between two parties. If you set these channels up into a large network, you can send tiny fractions of a cent for free. But there is a huge bootstrapping problem here: people need to (1) convert some money into cryptocurrency, then (2) choose who to create a channel with and then (3) create a channel on this network. Finally, once the content creator has received their coins, if they want to spend them outside the network, they have to close their channel, pay the network a transaction fee, and then convert their cryptocurrency back into their native currency.

Filling the vacuum

What is needed is a way to send small amounts of your native currency to content creators, and have that arrive in their bank account. In my opinion, the best way to solve the bootstrapping problem is to use what already exists: credit cards and web payments. The Web Payments API is a standard that lets people store their credit cards in their browsers, so they don’t have to enter them multiple times. Google Pay and Apple Pay use this standard also, so that iOS users will see a familiar Apple Pay prompt, and don’t have to enter their card numbers more than once.

The fixed fee problem is still there, but there is a good workaround. Imagine a third party service that can accept payment information for a 5¢ payment, then store those transactions up until the amount is above some minimum, like $5. After I read a hundred 5¢ blog posts, that $5 gets disbursed into the blogger’s account, and only then is the credit card processing fee incurred.

To be clear, this requires some recurring activity, people have to keep coming back and reading new articles, or listening to new songs, before those micropayments add up to a macropayment, so this is a low commitment relationship. If after a hundred blog posts, you lose interest, the blogger gets paid, but you don’t get stuck in a subscription that expects you to pay in perpetuity.

Why can’t we just start with subscriptions and then cancel if you lose interest? You can, but the low-commitment option allows readers a ‘free buffer’, where they have committed to paying if they keep coming back, but don’t actually get charged until they pass the first threshold.

The user experience

So what would this look like in practice?

The thing that shows up in your browser is called the payment sheet, it is a central part of the Web Payments API. A big advantage to the Web Payments API is that your credit card is saved at the browser level, not in some account with a password. Oh, that reminds me, this doesn’t require a password, you could just pay for what you want, and then not bother to log in, because the transaction is over.

The long term

The user experience here is still limited by the fact that we need to enter the CVC every time. It would be better if you had a budget, or a limit that would show up like a battery charge symbol: , and then as you browsed, that “money charge” would slowly drain until you needed to refill it. No ads, no passwords, just browse, read, and transparently pay for only what you consume.