Book Review: Atomic Habits

Atomic Habits is written so clearly that I have a hard time believing ‘James Clear’ isn’t a clever pen name. That clarity comes from experience and practice. His story about recovering from a major head injury and returning to sports is inspiring. His recovery is a big source of practical knowledge about how to build good habits.

Before I read this, I thought of habits using the goal/discipline model. You start by setting a goal, then you apply discipline in doing something repeatedly to reach that goal. But this book challenges that model. He quips:

Winners and losers have the same goals.

Instead of goals, we should be setting up systems for our future selves. You may be motivated now in the present, but future versions of you will have bad days, and you should make it easy for future you to repeat the desired behavior. You should make it easy.

The author doesn’t deny human agency, but he does acknowledge that we are shaped by our surroundings. We also shape our surroundings. So instead of depending on motivation and willpower to perform your desired behavior repeatedly, harness that motivation to reshape your environment. That will make the desired behavior easier to do.

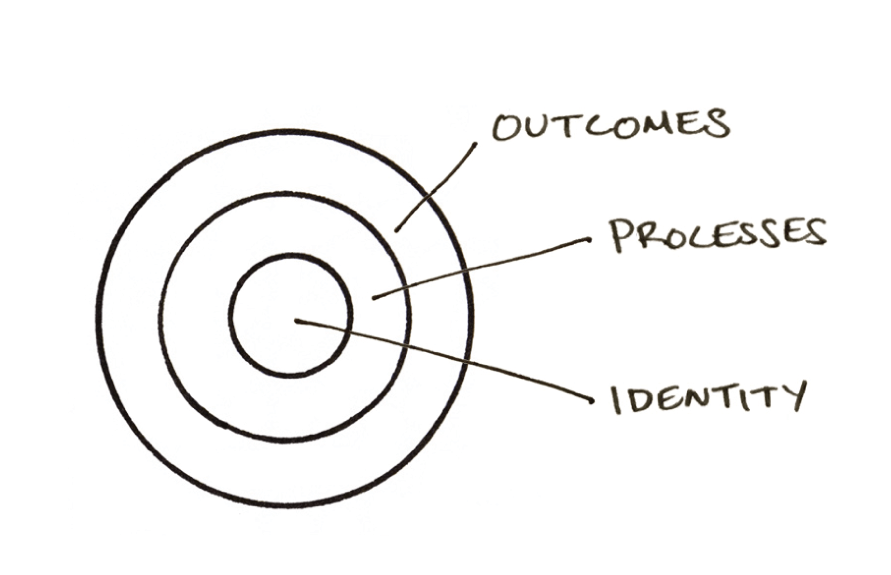

The most deeply weird and fascinating idea he introduces is identity hacking. He doesn’t call it that, I did. He presents an onion-like model of human behavior where the outside layer is outcomes. The middle layer is processes, and the center is identity.

This onion-layer model explains why goal/discipline habit formation so often fails. The reason is that it only tries to change the middle layer, processes. The reason we revert to our old behaviors so often is that we don’t go deep enough.

Going deeper in this case means changing your identity. Instead of trying to lift more weights, Become a bodybuilder. Instead of trying to donate more to charity, Become a philanthropist. Instead of quitting drinking, Become a teetotaler. James Clear argues persuasively that the key to building a habit is deciding the kind of person you want to be, then proving that identity to yourself with small, consistent wins. Those wins can be pitifully small at first, but they need to be consistent, and they need to grow. He even says “start with 2 minutes”. Going to the gym for 2 minutes every day is better than going 1 hour every week and skipping every now and then. Incidentally, this also explains why CrossFit™ is good, the people who join it and stick with it become the kind of person who does CrossFit, and talks about it all the time. While it’s annoying to us non-CrossFit people, cultish devotion to physical fitness is definitely effective. You have to kind of respect it.

Don’t go overboard with identity hacking though, I explore the question of how big your identity should be in an earlier post. Be very intentional about what you identify with. Committing to being labeled a certain way can have some benefits, but it has serious costs.

Once you work backwards from your desired habit to find the identity whose expression is that desired habit, you need to start taking actions that prove that new identity to yourself. This is a process of “proof of identity”. For example, I wanted to quit drinking recently, so I decided I was going to become a teetotaler and set up a habit tracker. Now every day I don’t drink, I check off the habit tracker and my streak increases. Seeing that unbroken streak of sobriety is a small win, and it grows over time. The way that habits grow over time is not just a linear streak of days, increasing one day per day. Habits tend to compound, like interest.

Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement. The same way that money multiplies through compound interest, the effects of your habits multiply as you repeat them. They seem to make little difference on any given day and yet the impact they deliver over the months and years can be enormous. It is only when looking back two, five, or perhaps ten years later that the value of good habits and the cost of bad ones becomes strikingly apparent.

For a primer on compound interest and the power of growth, see my earlier article compound growth.

Aside from identity and consistency, this book introduces a very useful operational model of human behavior, called the habit loop. I translated this model into JavaScript code:

// The Habit Loop

while(alive) {

// Problem phase

let cue = getCueFromEnvironment();

let craving = predictCravingFrom(cue);

// Solution phase

let response = respondToCraving(craving);

let reward = experienceReward(response);

updateAssocations(cue, reward);

}

This loop is running all the time. It can be picked apart and modified to make future you more likely to stick with your desired habit.

Starting from the first line, you can change the enviroment to give you the right cues at the right time. This he sums up as “Make it Obvious”, like for example, hanging your workout clothes near the door so you see them when you are near the door.

The cue feeds into a predictor, where your brain predicts the outcome of that behavior and you have some emotional side effects. Those emotions and cravings lead to a response. This is the choice part, where you choose what to do. You want to set up your environment to make the right choices easier, and the bad choices harder.

Finally, there’s the reward. If you went running, that’s an endorphin rush. If you saved money, it’s the number going up in your bank account. That reward then gets associated to the cue, re-inforcing the behavior.

Conclusion

James Clear has a template for how to build good habits, and how to dissolve bad habits. The long-term sustainability of those habits depends on altering your identity, something you should only do sparingly and after much reflection. He does a good job of talking about the downsides of habit formation as well. The book is well written, actionable, and thought-provoking. I never thought a self-help book would turn into a meditation on figuring out who you really are.