Book Review: Where's My Flying Car?

This book has two parts, one looks back and asks why flying cars never came to market, and the other looks forward to what possibilities lay ahead. The author has a background in chip design and nanotechnology, and even became a pilot so he could better evaluate the feasibility of flying car designs.

The autogyro, developed in the 1930s by Juan de la Cierva, was a promising candidate for a flying car. It was small, cheap, and gracefully descended if the motor failed. Harold Pitcairn was more of a businessman and de la Cierva was more of an engineer, the two worked together until de la Cierva’s tragic death in 1936. Juan de la Cierva died in a DC-8 plane crash on his way to Amsterdam. Pitcairn and the company pivoted towards helicopters after that, and after World War 2, the autogyro vanished to history.

The story of why flying cars didn’t take off is this: in the 1930s, the Great Depression and Juan’s death put the fate of the autogyro in Pitcairn’s hands. In the 1940s the war crowded out everything else. In the 1950s, Pitcairn was stuck in court, fighting the U.S. government over alleged patent infringement. In 1958, the FAA was created, and the regulatory environment around aviation became a lot less friendly to experimentation.

The author points to an example FAA rules that aren’t even about safety. There are process rules about who is even allowed to file the paperwork, and these create unnecessary delays while paperwork requests sit in queues at the FAA. Regulatory agencies like FAA and NRC write the rules, enforce the rules, and adjudicate the disputes about the rules. There aren’t the same checks and balances laid out in the constitution. The only thing limiting the power of these agencies is the clarity of the statute that congress writes. That is, when congress passes a law that the FAA has to go administer, if the law is vague, then the agency can fill in the details however it wishes.

Game Theory and Learning Curves

It’s easy to roll your eyes at the claim that “regulation destroys innovation” because it’s sometimes used as an excuse by companies to avoid having to spend money on safety. But aside from that occasional opportunism, there is a deep kernel of truth in that statement. Businesspeople have to weigh the risks and the rewards of a given decision. Regulators only have to weigh the risks.

Thinking about this in game theory terms, regulators are playing this game: if they approve product X and it leads to an accident, then they get penalized. But if X doesn’t lead to an accident, it’s neutral, because the Agency doesn’t get rewarded. If they delay X and impose more costs on it’s production, they can create more work for themselves and more work for the company being regulated. The way government budgets are allocated, agencies that use their whole budget tend to get re-approved for that amount, and if they spend less than their budget, their budget gets downsized.

| X causes accident | X doesn’t cause accident | |

|---|---|---|

| approve X | Agency gets punished | Neutral for Agency (or negative if quick decision justifies less budget next fiscal year) |

| delay X | Agency gets budget re-approved | Agency gets budget re-approved |

From this payoff table, you can see that there are no incentives for regulators to approve things, but there are incentives to delay. This delay adds an unbounded amount of time and cost to production.

Okay, so some delay is added while regulators decide whether to grant permission, what’s the harm in that?

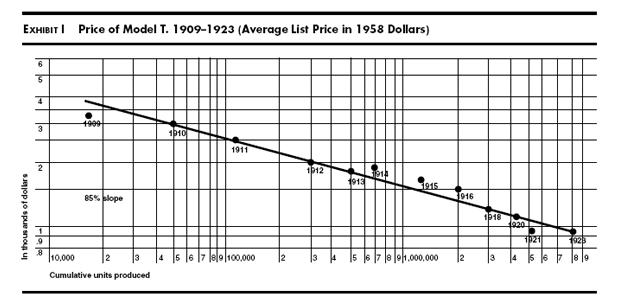

In order to appreciate why an unchecked, unbounded delay on production is harmful, we need to study a common pattern in production called a learning curve. Here is a chart show the price of a Model T from 1909-1923 (in constant 1958 dollars).

Notice that as the cumulative number of Model Ts doubles, the price lowers by some constant fraction. That means that if production grows exponentially, the price goes down exponentially.

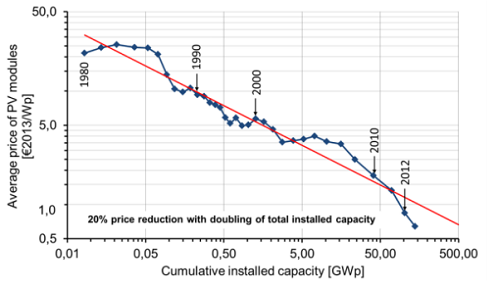

Another example of this is solar panels. When solar panel production grows exponentially, the price goes down exponentially.

The reason this happens is that producers learn by doing. They produce the first batch of goods, then get feedback from the market. They then use what they learned to produce better versions of those goods, faster, and at lower cost. If each year, the people producing these goods can improve by some fixed percent, like say 7%, then after 10 years, they will be twice as good. After another decade, they will be four times as good, and after 30 years, they will be eight times as good. This is the miracle of compound growth.

This is the virtuous cycle of improving production through market feedback. It’s capitalism at it’s best. It happens when producers can experiment freely, try things out, get market feedback and then iterate and improve quickly, to serve their customers and maintain that trust.

Now imagine that instead of trying new things and seeing how the market responds, they had to file a form instead. The form is with a bureau that is run by a small number of people who will probably not get fired for delaying getting around to your form. The form isn’t just for permission to sell your product, it’s a form to start a process that might end in permission, or end in more forms. While you are waiting on the regulators for permission, there’s a government shutdown, and while other businesses are operating, you are stuck waiting around for the bureau to get back to work and finish the process. The process turns out to take longer than you expected, your most talented and ambitious people are chafing at having to wait, and they quit out of frustration and take their talents somewhere else. Even if they stay, your customers won’t wait around forever. In this way, unchecked regulation can smother progress and destroy the learning curve.

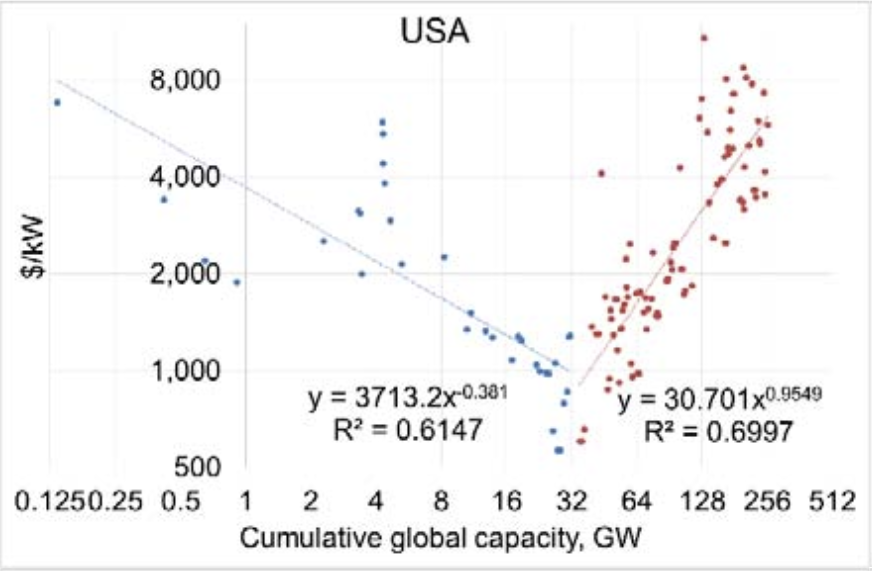

One clear example of this is with nuclear power, you can see the learning curve in action in blue, until there’s a sharp turn upward around 1975 (red). This is when the Nuclear Regulatory Commission was formed.

The NRC does an important job, to ensure that nuclear reactors are safe. Unfortunately, they use a (almost certainly false) model of radiation safety called LNT (Linear No-Threshold). Also, NRC uses a slippery standard with shifting goalposts called ALARA for “As Low As Reasonably Possible”. This ALARA standard inflates costs, and even though the fundamentals for nuclear fission are so excellent, this regulatory standard has the effect of pushing up production costs until they are in the ballpark of other methods of energy generation. For more on why nuclear energy has been made so artificially expensive, see Jason Crawford’s article Why Has Nuclear Power Been a Flop?.

The author reasons that we don’t have flying cars because during the window of opportunity between 1903 and 1958, the few promising threads of flying car development never made it to fruition. After 1958, the aviation industry became so heavily regulated that new attempts struggled to move down the learning curve. This kept them more expensive than they would have been if that virtuous cycle could have taken off.

Ending the flying car part on an optimistic note

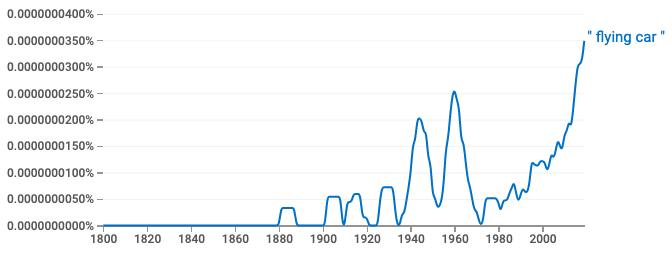

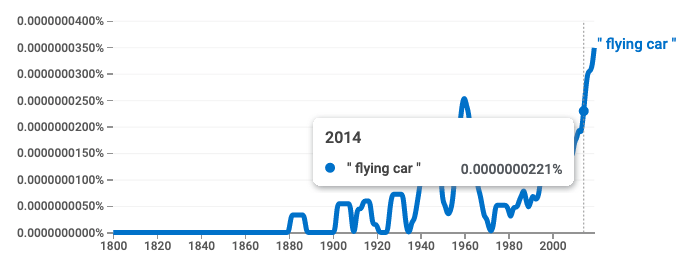

The part of the book that focused on why flying cars didn’t take off had more threads of analysis, but I’ll leave those out of this article, because honestly, I am kind of over it. I want to start looking forward, and this Google n-grams chart reveals an interesting trend:

You can see the 1880s Victorian “flying car” bump before there are any actual working planes. Then there’s another bump right around the Wright Brothers’ historic first flights (1903). There are a few more, and then it peaks in 1960 and crashes in the 1970s.

Notice how the recent spike in activity accelerates in 2014. This is right around when Peter Thiel said “we wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters”. There were a lot of think pieces and books that riffed on that. This book is one of those, but it’s the most impressively thorough one.

Another thing that changed around 2014 is the rise of consumer drones. The book only mentions drones once. It’s about how the protocols being developed will eventually make our manual air-traffic control system redundant. Quadcopter drones can be scaled up to a car-sized vehicle. The startup Joby Aviation is doing something like that and is aiming to have it in production in 2024.

Looking forward

The basic issue of regulations accumulating and creating a sort of process entropy, whereby it gets harder and harder to try anything new, has not been solved. The future success of flying cars will depend on the patience of investors, and the success of examples like Joby Aviation.

Energy and The Future

If you are with me so far, you might have gotten the impression that this book is all about flying cars. But it’s not! It’s also about how our energy usage hasn’t increased since 1970. The author theorizes that you can predict which sci-fi predictions will happen and which won’t by just estimating how much energy those sci-fi plot devices must use.

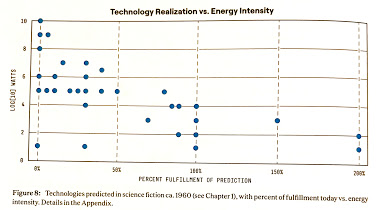

The author noticed a very clear pattern in which sci-fi predictions happend, and which didn’t:

Notice that very low-energy intensity things like pocket phones have exceeded expectations (200%, lower right), and very high-energy intensity things like manned space travel to Jupiter have not happened at all (upper left). But the upper right corner is totally empty.

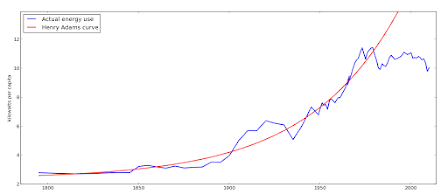

The author interprets this as a strong sign that the root cause of “The Great Stagnation” is energy use. He points out this exponential trend in energy usage since the Industrial Revolution began, called the Henry Adams curve:

Notice how energy usage flatlines around 1970. That is around when the OPEC Oil Embargo happens, and also when the NRC was created and slowed down the rapid progress in nuclear fission. We were on a path to abdundant, CO2-free electricity, but we strayed from that path because we got stopped by the cops (regulators). Now, 50 years later, we risk losing the great benefits of progress we inherited. Nuclear plants are being shut down early and leading to power outages during heatwaves. Renewable energy sources are growing, and fracked natural gas is abundant (in the U.S. at least), but efficiency, renewables and natgas are only enough to maintain our current lifestyles. We really should aim higher for our kids.

The idea that we should be dialing down our energy use for climate reasons presupposes we are using fossil fuels. While those fuels kickstarted the industrial revolution, we should be ascending the Kardashev scale and going nuclear.

The author believes that “nuclear & nanotech” once mastered, will deliver the same scale of improvement to human life that the Industrial Revolution did. This is because machines that can directly manipulate atoms could repair cells, allowing people to live forever. The nano-machines could set up nuclear fuel by sorting the atoms by weight. He has a lot of interesting theories about nanotech possibilities, but I’ll leave that to him to explain. He has a lot to say about why that didn’t happen.

The most interesting possibility for energy in the book is the possibility of nitrogren fusion. If we could reliably fuse nitrogen, then the waste would be silicon, which we could use to make semiconductors. Also, the fuel is literally the most abundant substance in our atmosphere, since the air is 78% nitrogen. This would mean that any vehicle could use air as fuel.

The reason this nitrogen fusion possibility stood out to me is that this kind of thing has happened before with that gas. Chemists had known that nitrogen was the major component of air long before the Haber process was discovered. The Haber process can make fertilizer out of air and hydrogen. Before that, people had to use poop as fertilizer, and guano was a huge deal. In the Guano had geopolitical significance before synthetic fertilizer could be created out of thin air.

In the 19th Century, geopolitics was about guano. In the 20th century it was about oil. In the 21st century, if we can master nitrogen fusion, then oil will be made obsolete, and the air will become a limitless resource for both fertilizer and fuel. I’m confident humans will find some other scarce thing to fight over, but this is the kind of possibility I want to go deep dive on and see how it might be done. This kind of breakthrough would put humanity back on the Henry Adams curve and decouple it from CO2 emissions, and it would open up the entire world. Any earthling with a private flying car that ran on air could go anywhere without ever needing to refuel.

There’s a lot more to the book, and I appreciate the way the author grounds it all in back-of-the-napkin math. After 2300 words, I feel like I could keep going, but I am starting to ramble, and you should just go read the book if you want to hear more.

The future could be unimaginably better than the present, and it will be, as long as humanity doesn’t prevent itself from ascending to higher levels of energy usage.