The Curse of Ideological Dimensionality

The left-right axis is so simplistic, right? People’s complex views can’t be projected down to 1-dimension, so Very Online people have invented higher-dimensional spaces to tag themselves in, like this political plane:

The two dimensions in that plane only cover social and economic issues, but what about technology, violence, spirituality, sexuality, or the bulldozer-vetocracy axis?

Vitalik Buterin, the creator of Ethereum, wrote a very good article arguing for this bulldozer-vetocracy axis. This is compelling because there are many real instances of left-progressives siding with right-conservatives in vetoing new housing units from being built. This prevents the housing market from absorbing new people who moved into an area and tends to drive up property values. The vetocrats want the built environment to stay as it currently is. The bulldozacrats want to smash old structures and build new ones and lean into the dynamism and vitality of a growing city. The standard terms liberal and conservative don’t really capture this divide in practice. A new axis is warranted. We need more dimensions.

In AI, machine learning and statistics, data is usually organized into high-dimensional spaces. To visualize this, imagine the familiar 3-dimensional space you are in now, you can specify a point by choosing a single reference point and then measuring three distances (length, width and height) relative to that point. In this way, you can describe any point in the universe with just three numbers we call coordinates: $$(x_1, x_2, x_3)$$

Now if you just add more coordinates you can still calculate distances and make shapes and use tools from linear algebra and geometry and calculus. For example, a hot new application of LLMs (Large language models like GPT-4) is Vector search tools. Vector search makes use of the mathematical structure of high dimensional spaces.

A tangent on embeddings and transformer models

LLMs convert sentences like “How can I write a USB device driver in C that will blink an LED?” into tokens, like

["How", "can", "I", "write", ..., "will", "blink", "an", "LED", "?"].

Then it converts the tokens to numbers. Each token is then mapped to a vector of fixed dimension.

$$\text{“How can I …. blink an LED”}$$

$$\downarrow$$

$$[\text{“How”},…,\text{“LED”}]$$

$$\downarrow$$

$$[1042, …, 72]$$

$$\downarrow$$

$$[v_1, v_2, …, v_k] \text{ where } v_i \in \mathbb{R}^n$$

Now, this encoding of the input sentence also needs the positional encoding of the vectors in the sentence. This is because vector addition is commutative: \(v_i + v_j = v_j + v_i\). Commutativity destroys the order of the original sentence.

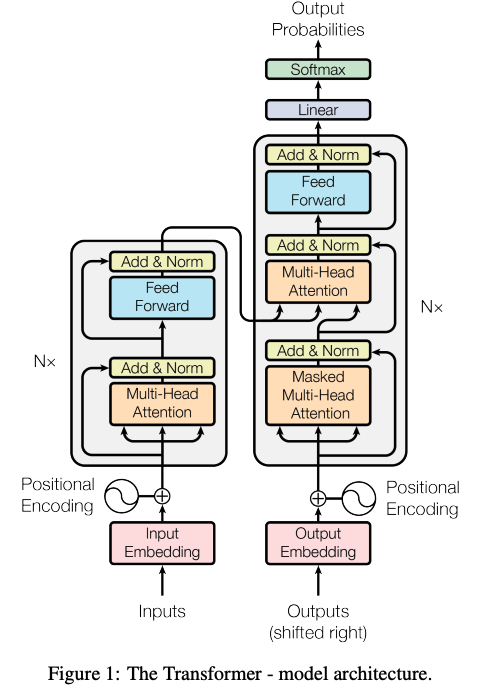

The way the positional encoding is done in the paper Attention is all you need (2017) is by using a Fourier transform-style encoding of the position. The position is a number \(p\) and then the positional encoding is:

$$PE_{(p, 2i)} = \sin\left(\frac{p}{10000^{2i/n}}\right)$$

$$PE_{(p, 2i+1)} = \cos\left(\frac{p}{10000^{2i/n}}\right)$$

So the position of the word “USB” in the input sentence will cause it’s positional encoding to have a lower wavelength than the one for “LED”.

Note that all the token embeddings \(v_i\) and positional encodings \(PE_p\) are all the same number of dimensions, this allows them to be added together. In the transformer model architecture from that paper, you can see how the embeddings are added to the positional encodings:

So LLMs represent any text data as a vector in an n-dimensional space \(\mathbb{R}^n\), this is the basis of vector search. Once you have this embedding, you can search for similar data, even if there are no common words between the original sentences. This is because the training of the transformer will capture semantic information in order to better predict the next token in a sequence.

Back to the curse of dimensionality

Okay, so now you have an idea how text data might be represented as points in a high-dimensional space. Here’s where we introduce the curse of dimensionality and talk about how this affects political identification.

The curse of dimensionality

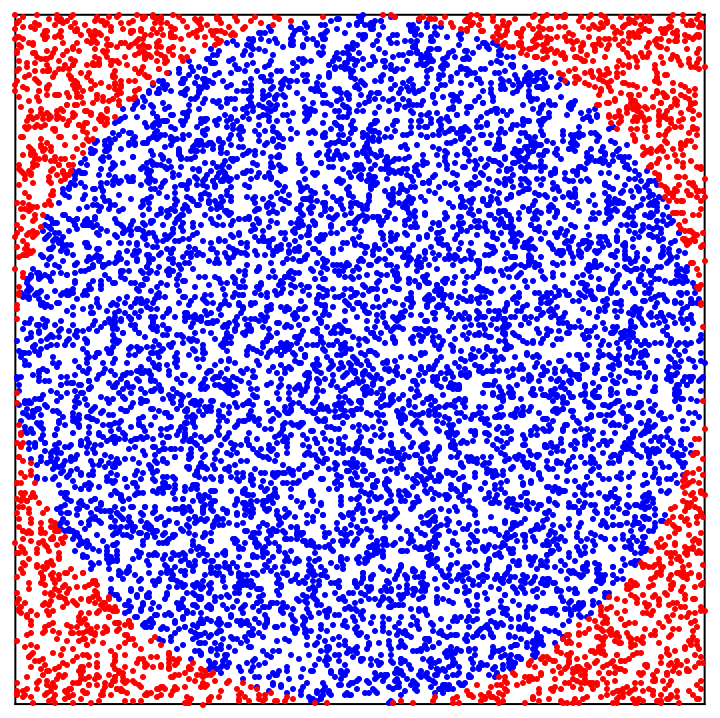

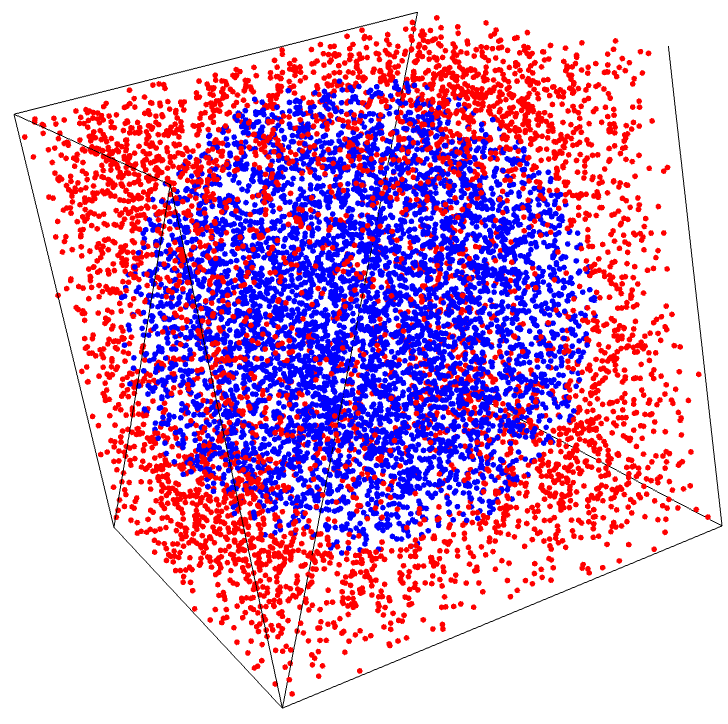

Consider an \(n\)-dimensional cube , with an \(n\)-dimensional sphere inscribed in it:

| image | dimension n = |

|---|---|

|

2 |

|

3 |

As the number \(n\) of dimensions increases, a larger and larger fraction of the points will be red points near the extremes . This is not a statement about any party or faction, this is a geometric fact. As the number of dimensions increases, most points are near the surface of the cube, not near the center. Think about how weird this is. In 1 dimension, if you randomly drop grains of sand, they land in a normal distribution, that is, most points are near the center.

The curse of ideological dimensionality

This means that if there is only a single dimension of political identification (left-right), then it’s easier to build a reasonable center in a democratic system. But as you increase the dimensions along which people can freely identify, you will end up with increasingly bizarre and extreme factions that make literally no sense but somehow embody a collective zeal that propels them to have actual political impact in the real world. There is opportunity in this dimensional freedom, but also obvious risks. My only advice to people worried about becoming some bespoke extremist is to keep your identity small.