Cybernetics in the Age of the Cloud

There’s an old saying:

There is no such thing as the cloud, there’s just someone else’s computer.

That saying is true on the object level, a cloud provider is just a service that runs your app on a bunch of computers that belong to the service owner, like AWS or Google Cloud. But while it’s true that there isn’t a cloud there, it’s also true in the same way that there is no “computer” there. The operating system provides a way to control a bunch of separate devices, like a CPU, a hard disk, a WiFi antenna, etc. The operating system’s job is to abstract over the hardware details and present the user with a view of those devices as a single unified system.

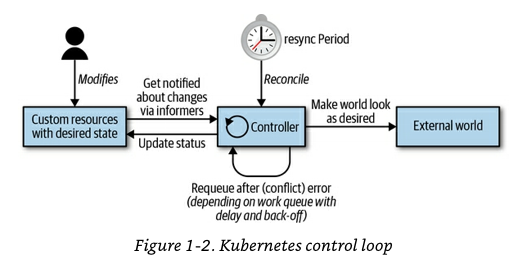

Kubernetes is like an operating system for a whole cluster of computers, so instead of managing \( n \) computers as individual nodes, the user can write out the desired configuration and the Kubernetes system will monitor the state of the cluster and decide which actions it needs to do in order to get the actual state closer to the desired state.

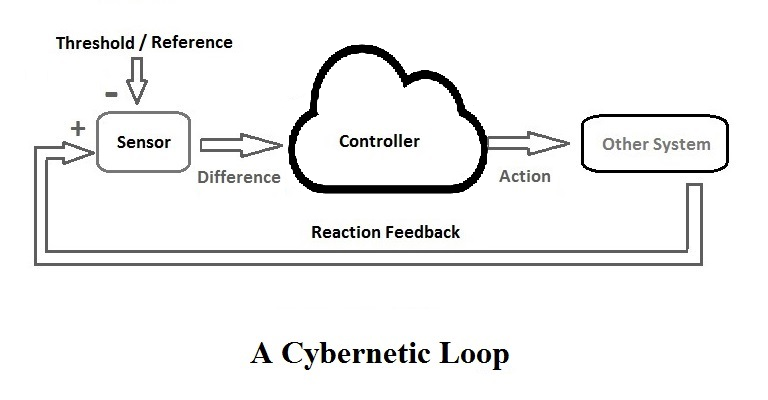

This is a closed-loop control system. The discipline of control theory grew out an interdisciplinary movement from the 1940s called Cybernetics. One of the first Cyberneticists, Norbert Wiener, wrote Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. The big idea in the book is that complex systems, whether biological, social or technological, are self-regulated by the feedback of information.

The original reason Wiener’s team was assembled was to develop an intelligent gun that would track a moving aircraft. The philosophical work of cybernetics was free-riding off of cybernetics’ applied military purpose. The narrow goal of developing a theory of control systems for intelligent weapons was accomplished. The war effort also accelerated the development of computer science. Luminaries like Alan Turing and Jon von Neumann worked directly on many problems that helped the Allies win World War 2. Computers exist partly because we needed a better way to blow up our enemies.

Rich Hickey has a memorable quote about data and computers:

If you put together two pieces of data, you get data. If you put together two computers, you get trouble.

The purpose of an OS is to unify a bunch of devices. The trouble Hickey was referring to came from the lack of such unity when working with multiple computers. Network protocols succeeded in allowing the internet to be born, but they are awkward. In order to connect two computers, a programmer has to create a socket, bind the socket to an address and port, then accept messages, then deal with buffering, packet loss, errors in transmission, etc. etc. Also, depending on the topology of the network, it may not be possible for two computers to communicate directly with each other, so they may need a third party and possibly a custom protocol to establish a direct peer-to-peer connection.

One way to unify a fleet of computers came out of Bell Labs, where Unix was created. It was called Plan 9. The big idea was to make everything a file. The GUI, other computers, literally everything was represented as a file. Then, if you wanted to control multiple computers, you would just simultaneously write a file to multiple locations in the filesystem.

Plan 9 never took off, but one of the Plan 9 developers, Rob Pike, went to Google and developed the Go programming language. Google then used Go in their early open source versions of Kubernetes.

The trouble of putting many computers together was a big enough problem that multiple teams of geniuses have attempted to solve it.

The immense growth potential of software means that successful companies have to keep adding computers to their fleets as their customer base grows. Amazon, Google, Facebook and Uber all solved this problem in slightly different ways, but there were a few things they did in common.

All these companies defined new abstractions like autoscaling groups and redundant databases that would prevent data loss when one of the computers in the fleet inevitably crapped out.

Google’s internal system, Borg, was named after the hive-mind aliens from Star Trek that identified as a single entity, annexing individuals into their hive-mind and erasing their independence.

They open-sourced Borg and eventually settled on calling it Kubernetes, because the operating the system is like driving a container ship. The Greek word for “pilot of ship” is κυβερνήτης (Kubernetes). The Greek word “kuber” is close to the english word “governor”, or boss. The root word of “gubernatorial” is “gubernator”, which comes from gubernare (to steer, or to govern), which comes from the Greek word kubernan.

The founders of Cybernetics were studying this same kind of thing before computers, and used the same word κυβερνήτης as an inspiration. “Cyber” derives from “kuber”.

The Kubernetes system that exists today is built on a really simple control loop with feedback, in the cybernetic tradition, but for a digital system, not an analog one.

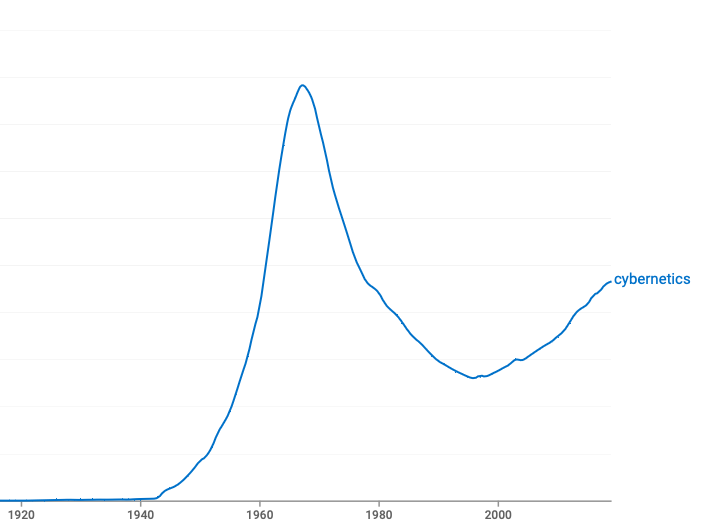

There’s a great essay by Peter Asaro called “What happened to cybernetics?” that answers the question of why we don’t use this term any more. If you look at a Google ngrams search of the term “cybernetics”, you will see it peaked around 1970.

Did it disappear because it failed in its revolutionary goals, or did it disappear because it was so successful that it is now merely taken for granted?

He gives three different answers, based on what you think cybernetics was.

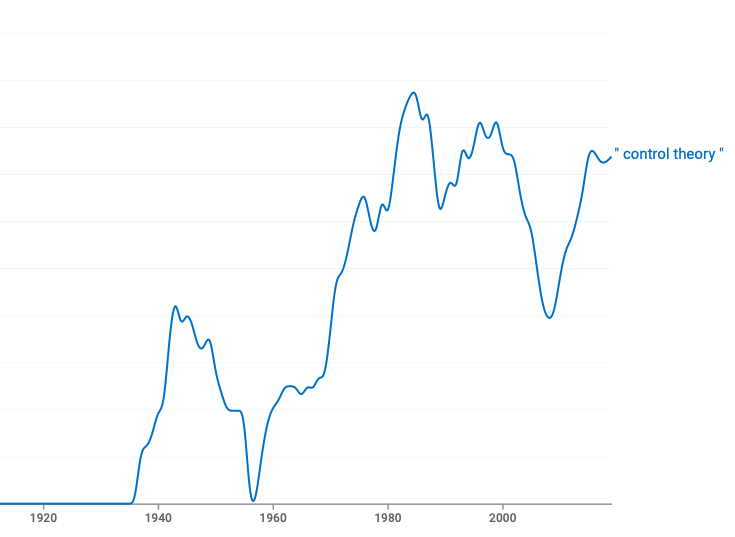

The narrow view is that cybernetics is the study of negative feedback loops and their centrality in so much of nature. This narrow view is now common knowledge in engineering disciplines and the social sciences. It’s familiar enough that it almost seems banal. If this is what you mean, then cybernetics is not a useful term because it’s too vague, and “negative feedback loops”, or “control systems” are better because of their specificity.

If you do a search for “control theory” on ngrams, you will see it is still widely used:

The broad view is that cybernetics was a new scientific paradigm:

In its self-centered retellings of the history of science and human civilization as leading ultimately and inevitably to the science of cybernetics, it created its own mythology. The age of matter was passing away, and the age of form was coming. The age of industry, symbolized by the steam engine, was giving way to the age of information, symbolized by the computer. And where physics had promised to give humanity domination over matter and energy, cybernetics now promised to give humanity domination over information and organization. This was how cybernetics saw itself as replacing physics as the science upon which all others would be based. Cybernetics was thereby nothing if not radical and revolutionary. It sought to overthrow the entire scientific order as handed down from Newton, and with it the social and political order.

This new paradigm has preceded the rise of the microprocessor, the internet, control of RNA and DNA sequences, and the broad application of machine learning to industry.

If we accept this broad view, then we are already living in the Age of Cybernetics, though maybe we just call it the Age of Information. It does not matter that nobody practices anything called ‘cybernetics’ because everybody is always already cybernetic, everywhere and all the time.

Finally, he explores the third view, the “Internal view”. The basic idea of self-regulating systems is a predecessor to the idea of artificial intelligence, and the political rift in the AI research community around symbolic versus connectionist approaches caused funding to be diverted away from the more “cybernetic” of the two approaches.

Asaro also goes into something he calls “2nd order cybernetics”, which was lead by physicist Hans van Foerster. His flavor of cybernetic thinking was was inspired by the Uncertainty Principle from physics. The observer is part of the system system being observed, and that creates fundamental limits on what can be known and controlled by a system.

In 1958 he started a lab doing cybernetics research, the Biological Computer Laboratory (BCL) at the University of Illinois. One of the researchers at BCL, Stafford Beer, was tapped by Chilean president Salvadore Allende to reorganize the Chilean economy around a cybernetic vision with a centralized computer, all under the direction of Allende. The CIA-orchestrated coup d’état that installed Augusto Pinochet saw the end of this applied cybernetics project, but the legacy of that project lives on in the successful tech companies that invented the cloud. That legacy is explored beautifully in this Palladium Piece: How Capitalist Giants Use Socialist Cybernetic Planning by Nicolas Villarreal.

The three views Asaro gives in each of his answers are delivered like Golidlocks’ porridge: too narrow, too broad, just right! The last one is nuanced and has threads of history that lead from the atomic bomb being developed all the way to Google’s development of the cloud. It’s the one that’s situated in history, and tested against the real world.

After exploring these three answers, Asaro concludes, cybernetics “ate it’s own tail”:

Just as 2nd order cybernetics brought itself into existence autopoetically, it destroyed itself by failing to believe in itself any longer. But it stands ready to rise from the ashes and be reborn–anywhere, anytime–through autopoetic love, or through a cocktail making robot who begins to question its own existence and motives.

While this addresses the self-conscious movement of thinkers and researchers who “do cybernetics” he also adds that cybernetics is an ontology. An ontology is a philosophy of what exists. The ontology of Newtonian physics contains solid matter, gravitational forces, and light. The ontology of quantum field theory contains scalar fields that spread out over all of space and time. The ontology of cybernetics contains feedback loops of information.

Fundamentally, cybernetics is a new ontology. Andy Pickering has called it an ontology of becoming. The universe is not made up of matter, particles or energy. Nor is it made up of ideas, words, and symbols. It is not numerals, or universals, or plenum, or atoms, or monads. The world is made up to feedback loops of information. Not bits and numbers, calculations and data. This is the mistake of those who underestimate information, the delusion that information is static, stable, capable of being captured and controlled. Information is dynamic, changing. Information flows. It bears reflecting on the fact that information is measured on expectation and it is the message which is least is expected which carries the most information. The most predictable message is the least informative.

The ontology of cybernetics is fundamentally temporal. It is closer to “Presentism” than eternalism. I wrote more about this divide in the philosophy of time here at Time in Physics.

Kubernetes has an open-ended ontology of its own. New things can be defined and added through CustomResourceDefinitions (CRDs). These new resources are then automatically controlled by the main control loop. This allows people to expand the set of things that Kubernetes will handle for them.

What is so exciting about Kubernetes is that it puts these cybernetic ideas to use in a way that simplifies developing software for billions of users. The standardized, open-source nature of the kubernetes distributions like k3s, microk8s and RKE means that no one company or country has a monopoly on this power. It’s something that anyone with a little hardware and a little knowledge can put to use. It’s both an engine of further centralization and a way of creating new centers. Those new centers are set up to grow. The next billion-user application could start with a high school kid running k3s on a raspberry pi.