The Topology of the Tower of Babylon

The story “The Tower of Babylon”, by Ted Chiang, is the first example of topological fiction I’ve come across that wasn’t obnoxiously about topology from the start. I’ve read fiction before, like Flatterland by Ian Stewart, that was styled after Edwin Abbot’s classic 1884 story, Flatland. Flatterland explores non-Euclidean geometry, fractal geometry, and topology, all using the classic Flatland tropes. I’m familiar with the genre. But Chiang’s “The Tower of Babylon” had the gravitas of a biblical story, with the subtlety of a proper piece of literature, and climaxed in the realization of a deep topological truth: that a world can be finite, but have no boundary.

The Tower of Babylon starts out in Babylon, in the time that the book of Genesis was recording. The protagonist was an Elamite named Hillalum. As the story went on, Hillalum saw the construction of the tower of Babel as it rose from the city of Babylon and finally hit the firmament of heaven. He and his team, in cooperation with the Egyptians, tunneled up through the granite-like firmament to try and penetrate into heaven. They hit the waters, the original waters in the book of Genesis that were separated from the waters below. They seal the tunnel and Hillalum is trapped above. He barely survives, and keeps traveling up until he reaches dry ground. Thinking he is in Heaven, he is confused when it looks like Earth. He finds another man walking nearby and asks him where it is. He says it’s Shinar, which is on Earth. Hillalum realizes he’s traveled in a loop, from Earth all the way up the tower, through the firmament and back to Earth, with no miracles occuring along the way. At no point did Yahweh move him from heaven to earth, he simply followed a path and it lead back to where he started.

This is an example of what topologists would call a non-contractible loop. A contractible loop would be like walking in a circle on the surface of the earth. No matter how large that loop is on the surface of earth, you can continuously shrink it until it’s finally a point. But if you traveled along Hillalum’s path, it would not be possible to shrink it down to a point, since it “wraps around” the world and leads men back to earth after their technological ascent up their tower. That loop can’t be contracted because space itself conspires to prevent it.

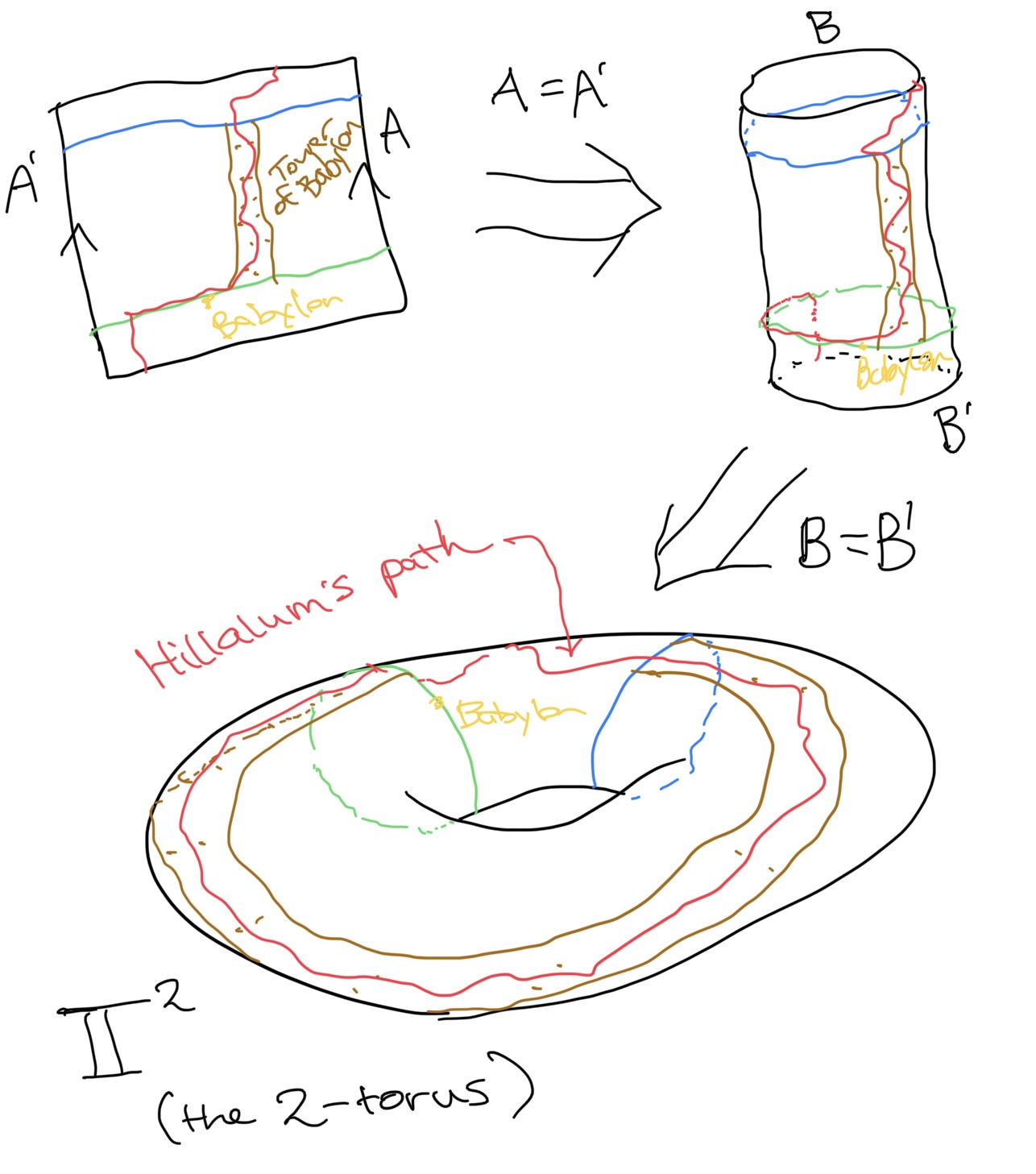

To visualize this, Hillalum imagines a cylinder seal, but there’s another step you can take to make a 2-dimensional space totally finite and with no boundaries, it turns the cylinder into a torus:

The red path is Hillalum’s path. It starts in Shinar, goes up a constructed tower to heaven, runs into the firmament that divides the heavens from the earth, bores through the firmament, but exits in Shinar. All the while, there are no miracles or anything that interferes with the continuity of space. This is like if a Flatlander made a large tower on a 2-dimensional torus and discovered that it lead right back to where it came from. It is in a finite 2-dimensional space, with no boundary.

The world that Hillalum inhabits is finite and without boundary. It is 3-dimensional but has the same basic structure as the torus: travel far enough in one direction and return to where you started. But also has the existence of non-contractible paths. That’s what makes it a torus and not a sphere. Spheres are such that all of their loops are contractible.

The topology might not have been THE POINT, but I think it was a brilliantly told introduction to that important topological idea (finite without boundary). And the point of that idea being explored was to probe how a god could set a world up so that it’s inhabitants didn’t have any arbitrary boundaries. Even the firmament was like a fence. Not a real boundary, it was penetrable. But even when you penetrated the boundary, the place you ended up was right where you started.

This story is currently my favorite example of this idea, of how a space can be both finite and boundless.