Book Review: Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

This book develops a theory of a cyclical pattern in the economy. The pattern describes how certain new technologies spread to become a whole new way of structuring society. The author Carlota Perez calls this a technological revolution and it’s associated “techno-economic paradigm”.

In this review I want to summarize her theory using less jargon. Even though the book reads like an academic text, and the jargon is used consistently, I want to dig into the idea in more common language.

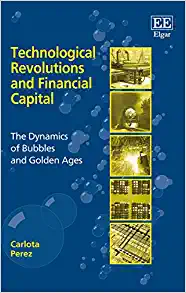

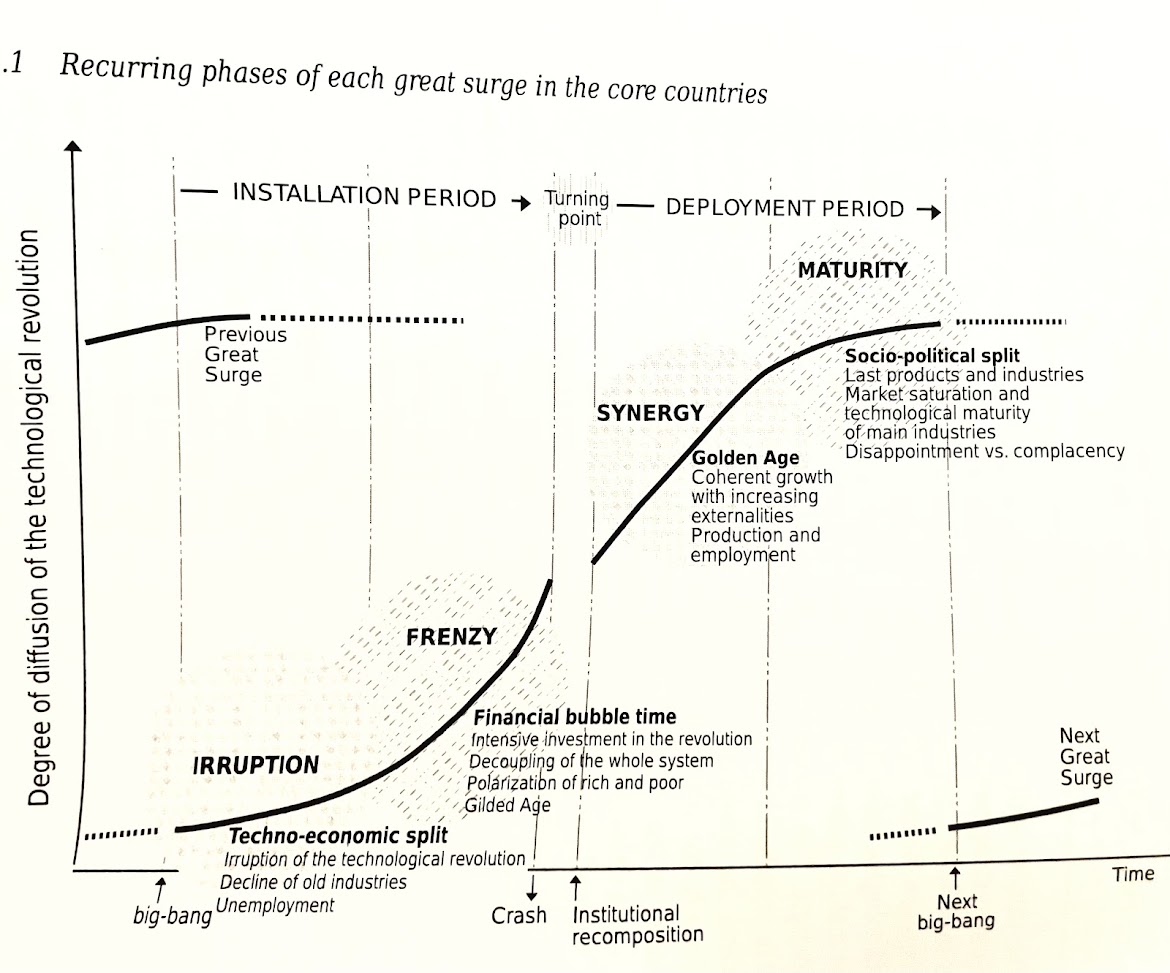

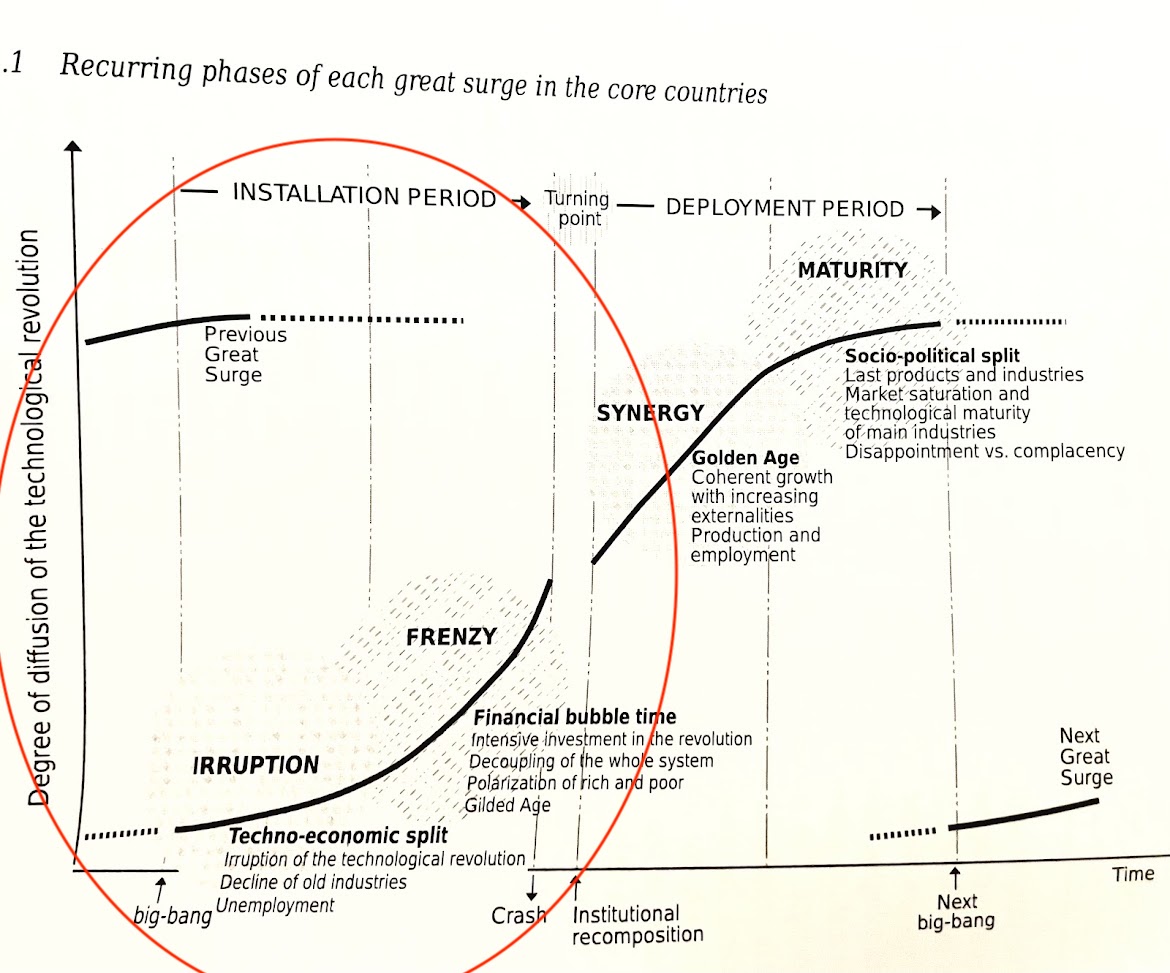

The lifecycle of a new revolutionary technology follows an S-curve trajectory like this:

The cyclical pattern has a period of around 50-60 years, and it starts with a new technology becoming commercially viable. This is the big bang event that kicks off the beginning of a new cycle. Examples include James Watt’s steam engine (1774), Henry Ford’s Model T (1908), or Gordon Moore’s microprocessor (1971). The big bang and the next 10-15 years are the Irruption phase. This is when the technology is driven by experimentation and excitement of the engineers and operators developing the new tech. This catches the attention of financiers, who are usually bored with the existing mature industries.

When Finance sweeps in and accelerates the spread of this new technology, this leads to the Frenzy phase. During the frenzy phase, financial capital decouples from production capital, creating an asset bubble. Historical examples include the 1920s (Frenzy phase of the 3rd great surge, of oil & cars), and the 1990s (of personal computers & the internet). During the frenzy phase, the technology and it’s associated way of structuring business is “installed” throughout the core country where the big bang event happened.

By allowing the new technology to grow faster than the fundamentals, it hastens the societal upgrade that will occur after the crash. By the time of the crash, it’s already spread around enough that a new “common sense” has formed.

The reason bubbles may be necessary is that established industries can use the power of the legal system to entrench themselves further and snuff out any new competitors. The sheer speed of the transformation that bubbles enable is the solution, simply execute faster than the incumbants can respond.

When the bubble pops, the frenzy phase ends. The popped bubble leads to a larger crash. The crash leads to the turning point, where social and political forces come in to clean up the mess. If done responsibly, this leads to new institutions and regulations that can re-couple finance and production, and lead to the Synergy phase, where there can be much broader-based growth, with rising wages and rising productivity at the same time.

Historical examples include the Wall Street crash of 1929, for example, look at Chrysler’s earnings around that time:

| Chrysler | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earnings | 5.07 | 6.55 | 6.80 | 4.94 | 0.05 | 0.33 |

| Dividends | 2.25 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 |

A more recent example is the Dot-com crash of 2000.

After the crash, political forces are prompted to respond to the crash. This point is an opportunity to re-couple finance to production, and to enable the conditions for broad-based growth. This turning point marks the end of the Installation period.

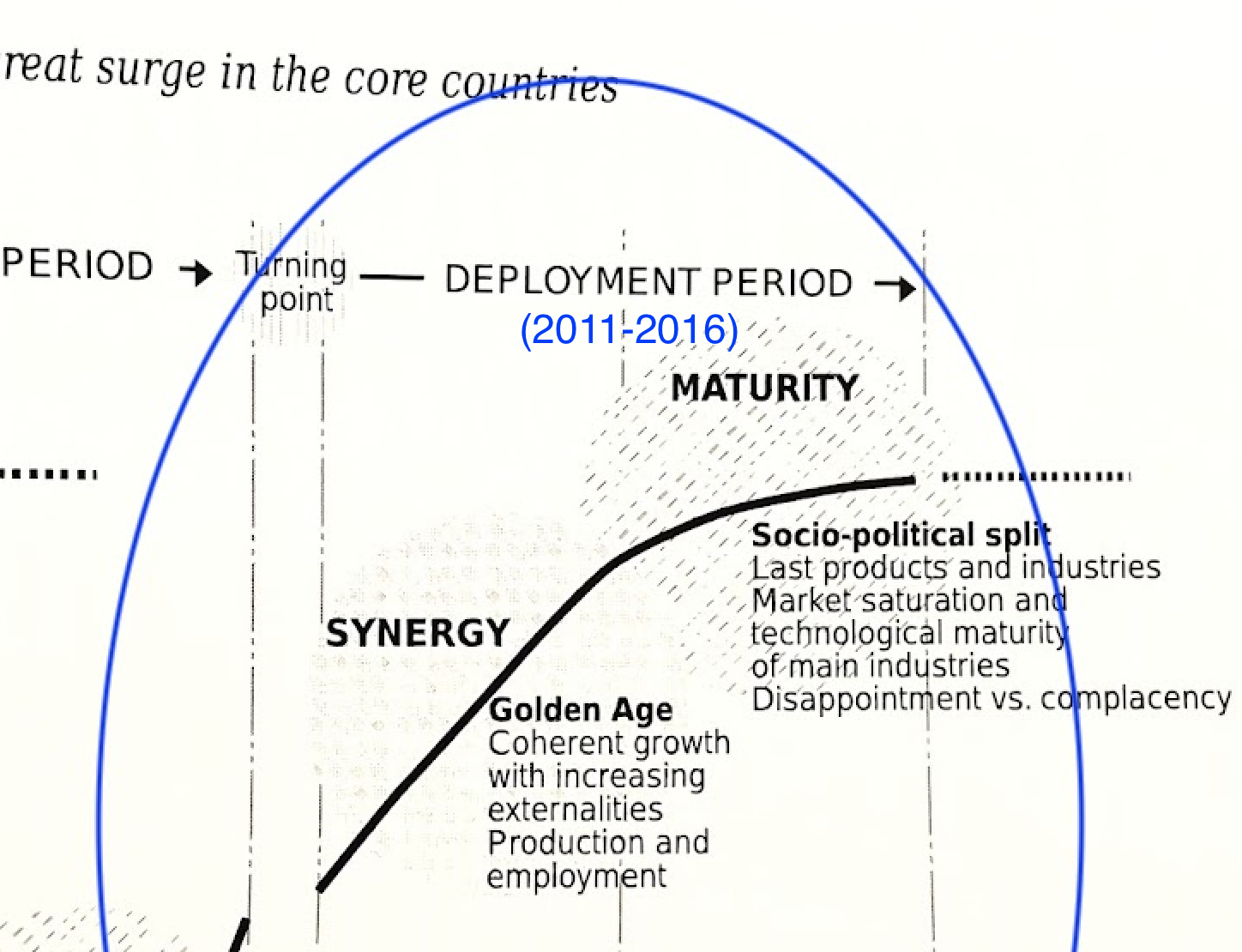

After the turning point, the Deployment period begins.

The first 10-15 years of the deployment period are the a “Golden Age” of broad-based economic growth, driven by real production, with a virtuous cycle of rising wages and rising consumption of products from the new industries.

The last half of the deployment period is maturity. This is when the new industries become the incumbents. This is also the time when growth slows down, companies consolidate and merge, finance gets bored, and the seeds of the next cycle are sewn.

Testing the model

There are four complete historical examples that informed the Perez’s model, and an emerging fifth one. To test the model, we should examine these examples, then make some predictions about the current one.

| Technological Revolution | Core Countries | Years | Crash |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial Revolution | U.K. | 1770-1830 | Canal panic 1797 |

| Age of Steam & Railways | U.K. → U.S. | 1830-1875 | Railway panic 1847 |

| Age of Steel, Electricity and Heavy Engineering | U.S. & Germany | 1875-1920 | Panic of 1893 |

| Age of Oil, Cars and Mass Production | U.S. → Europe | 1910-1975 | Wall Street crash of 1929 |

| Age of Information | U.S. → Europe & Asia | 1970-? | Dot-com crash of 2000. |

The four complete examples match the model qualitatively, and each of these revolutions lasted about half a century. The theory is not just about correlations, but attempts to draw a cause-effect link between the forces of technology, finance and government on the one side, and the boom/bust/golden-age/maturity cycle on the other side.

To test the model, we can make predictions about the end of the maturity phase of the Age of Information. Let’s get specific. The crash and turning point happened around 2000. The synergy phase saw the rise of the FAANGs, or Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google. I am going to attempt to place the end of the synergy phase.

The end of the golden age of the fifth surge

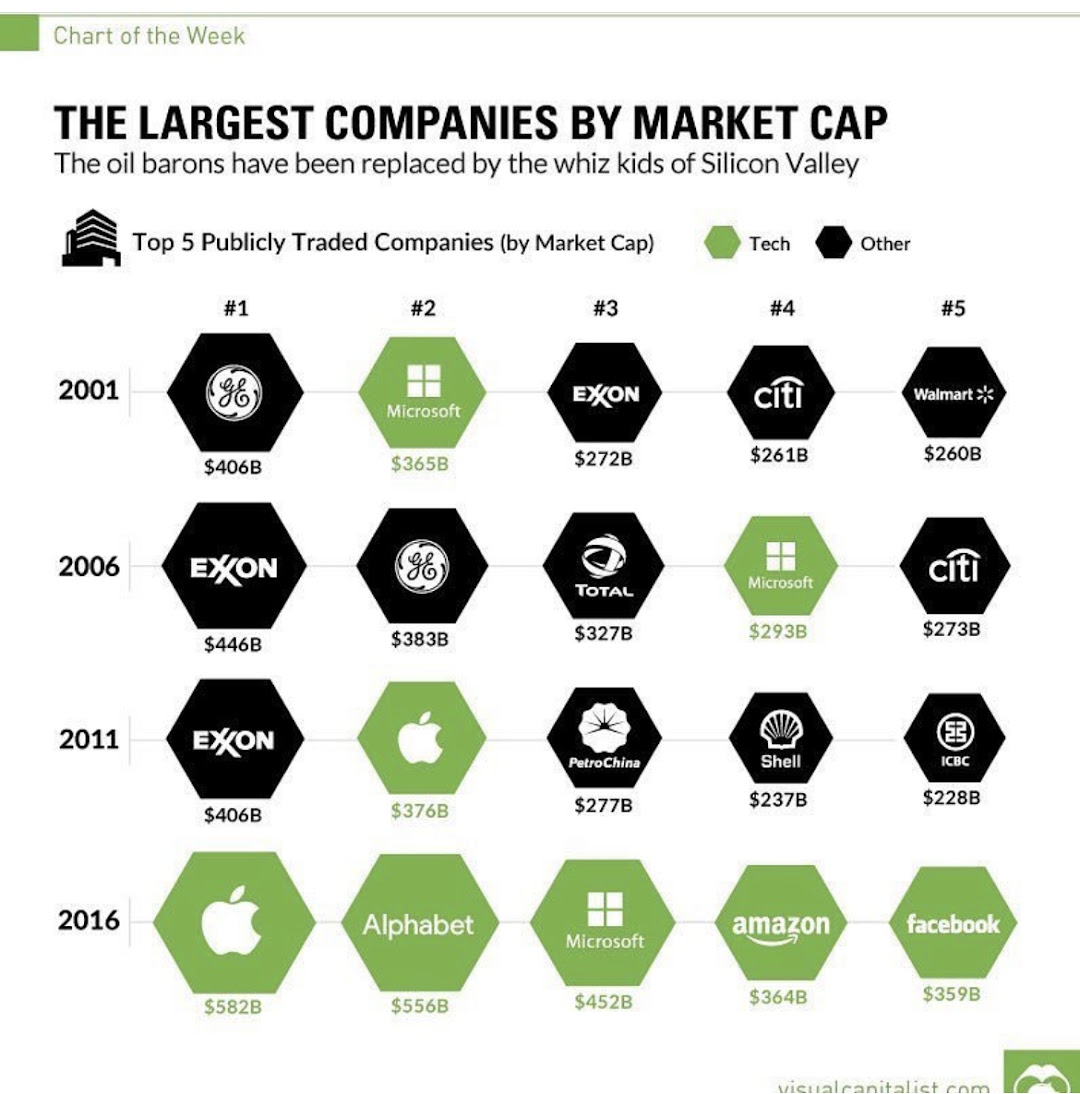

I remember sharing this chart on instagram in 2016 from Visual Capitalist. It shows the five largest companies by market cap (which is the value of all the stock for a company added up). Notice that from 2001-2011, the top 5 included oil companies like Exxon, Shell and PetroChina. These are the incumbents of the previous revolution, the Age of Oil & Cars. Then between 2011 and 2016, you see a flip, where the winners of the Age of Information make it to the top. Apple, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook become the new incumbents.

I estimate that the transition from the synergy phase to the maturity phase happened between 2011 and 2016. Since the crash was 2000, that puts the synergy phase at about 10-15 years.

If each phase is 10-15 years, then that puts the end date of this maturity phase between 2021 (10 years after 2011) and 2031 (15 years after 2016).

If we were already in the maturity phase, then we would expect:

- slowing growth of the FAANGs

- consolidation of the industry

- investors getting bored and going elsewhere for returns

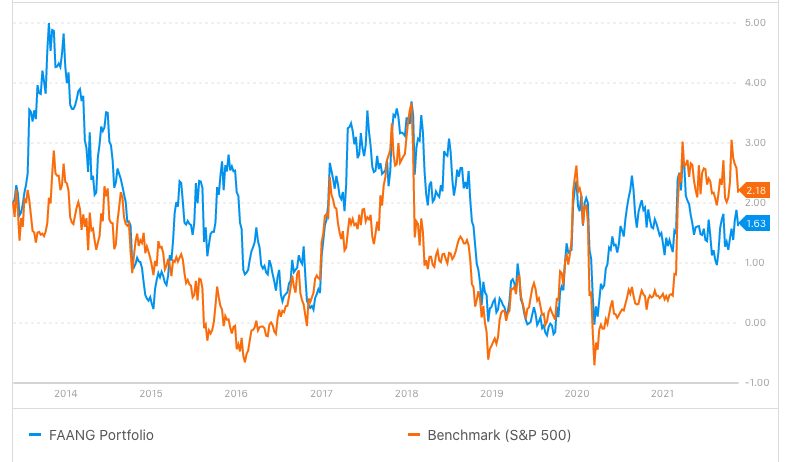

1. Slowing growth of the FAANGs

This has occurred, as can be seen by this chart of the growth of a FAANG ETF against the S&P500:

2. Consolidation

You can see a nice visualization of the largest mergers & acquisitions of the FAANGs here from Visual Capitalist, but in order to test this model, there should be evidence of increased consolidation in the information technology industry.

This Washington Post interactive on FAANG mergers and acquisitions shows just that.

And finally, are investors getting bored with FAANGs?

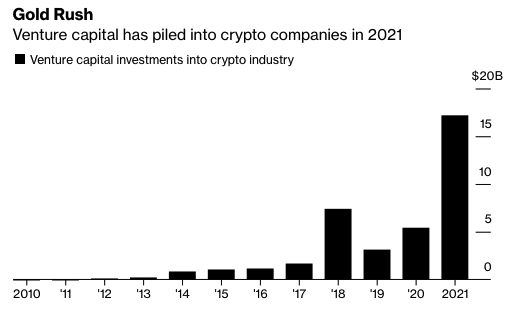

3. Investors getting bored with FAANGs

The SPAC boom of 2020, biotech and the new VC in cryptocurrency and web3 are consistent with the idea that investors are looking for more adventurous sources of returns.

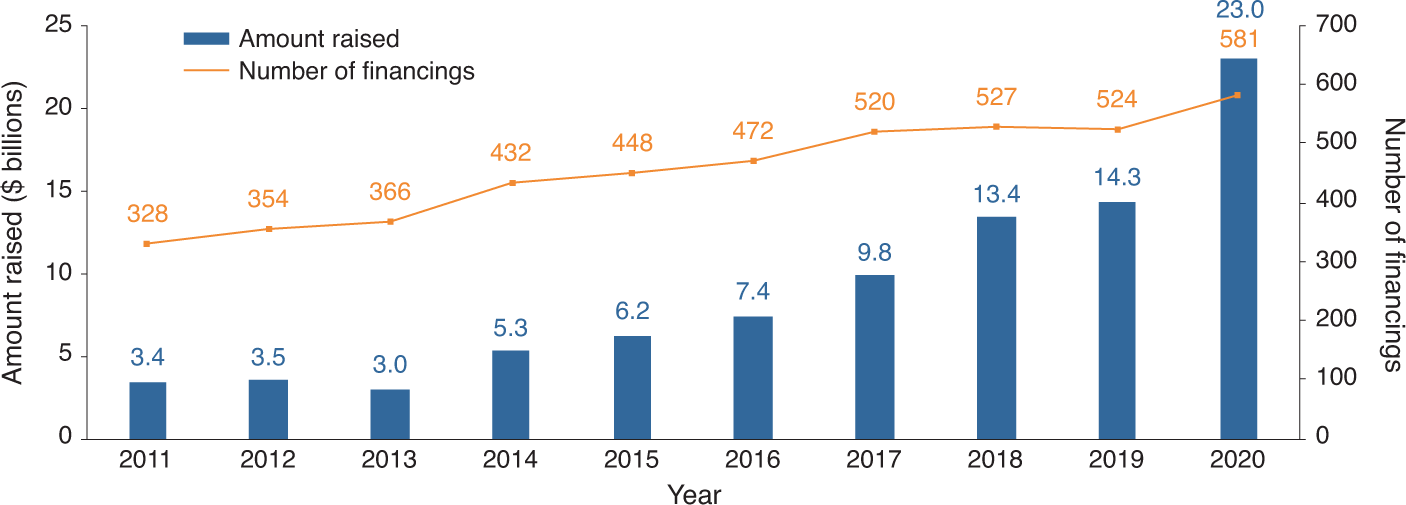

Crypto investment:

Biotech investment:

Summary: when is the “end” of the Age of Information’s great surge?

Perez models the dynamics of these great surges within the core countries where they emerge. The technology spreads outside the core countries, so these transformations don’t have clean endings. However, the great surge in the U.S. that started in 1971 with Intel’s microprocessor will come to an end. The effect of this will be that computer chips and software will become essential backbones of the economy, and no longer be a special source of growth here.

One piece of evidence of maturity is that a semiconductor shortage has caused automobile manufacturing to stall. The Age of Oil & Cars gave way to the Age of Information, and the lack of chips has now hobbled the production of cars.

So I tentatively put the end of the Age of Information at 2026, half way between now and 2031. There still feels like there is room for growth (just look at Amazon).

What’s next?

The author suggested that maybe biotech was going to be the source of the next big bang event. The recent boom in biotech investment certainly supports this. The whole COVID-19 pandemic was tamed because of the effectiveness of mRNA vaccines.

It’s hard to know which event will be the next big bang until there’s a frenzy, and policymakers usually don’t notice until there’s a crash. It’s possible that the big bang event in biotech has already happened. The two candidates are CRISPR-Cas9 in 2013 and the deployment of mRNA vaccines in 2020.

It’s also possible that the next big bang hasn’t happened yet. Perhaps some combination of gene editing, a protein folding AI and DNA printing will enable a new form of molecule-scale manufacturing that would transform medicine and materials science. The reason this seems promising is that proteins do all the work inside of cells. Proteins are the structure and function of life, DNA is the instructions to build proteins.

Candidates for next big bang:

-

🧬 Organic nano-manufacturing (protein folding AI + CRISPR gene editing + DNA printing = tiny protein factories)

- If the protein folding AIs get good enough that engineers can input a protein design into it and get a sequence of DNA as output, they can then print out the DNA sequence, use CRISPR to edit the sequence into an organism like yeast, then those yeast will act as little protein metafactories which print out proteins which are their own nano-factories. This could lead to new materials, new forms of energy (think modified photosynthesis tailored to human applications), new ways of sequestering CO2, new medicines, etc.

-

🚀 Affordable space activity (zero-g manufacturing, space tourism, asteroid mining)

- SpaceX and Blue Origin are both bringing down launch costs, and Varda is a startup that is aiming to do manufacturing in space. There’s also space tourism, asteroid mining, and reliable solar energy. Opening up a business district in space may very well be the next great technological revolution.

-

🤖 Robotic automation

- This one depends on AI and robotics advancing to a point where they are at least as capable as the average human, and more importantly, cheaper

- This would turn labor into capital, and the only remaining economic role for humans would be therapy, entertainment, luxury servives like massage, and investment. If robots really do get good enough and cheap enough to do all human work, then all humans can own shares in the robot companies and live off the passive income.

- Balaji Srinivasan has been thinking about this for a while, in his view:

- 19th century saw the move of most labor from farming → factories

- 20th century from factories → offices

- 21st century from offices → micro-hedge-funds, where the primary application of human labor in the economy will be directing investment

- Balaji Srinivasan has been thinking about this for a while, in his view:

-

🌟 Fusion energy

- If engineers can finally get more energy out of a fusion reactor than is put in, then it will cause the price of energy to drop so low, that entirely new forms of activity become viable.

- For example, fertilizer will no longer depend on a supply of natural gas

- Water will become abundant, since it can be desalinated from the ocean

- Vertical farms could become competitive with traditional ground-based agriculture. Currently they consume too much energy to be viable

- New frontiers on earth open up. Places in the middle of the desert, or on Antarctica can be developed and turned into livable places with enough temperature control, desalination and vertical farming. This could enable intentional communities to form new cities and experiment with new governing regimes

- If engineers can finally get more energy out of a fusion reactor than is put in, then it will cause the price of energy to drop so low, that entirely new forms of activity become viable.

-

🧠 Brain-computer interfaces

- Higher-bandwidth control of computers can allow for increasing human intelligence by integrating it with machine intelligence. Neuralink is currently working on this.

-

🕶 The Metaverse

- Okay, hear me out. If AR/VR headsets can be made small enough, they could open up new workflows that dramatically increase productivity. One person who is exploring this is @asteroid_saku.

- Real world experiences and virtual experiences can be integrated more deeply, opening up shorter feedback loops between idea and demos

- Mark Zuckerberg is also going all-in on this and even renaming Facebook to “Meta”. In Zuckerberg’s view, this will be a new virtual economy that is unshackled by geography and can grow to infinity.

- The next big-bang might be AR glasses that are not awkward to wear

- Okay, hear me out. If AR/VR headsets can be made small enough, they could open up new workflows that dramatically increase productivity. One person who is exploring this is @asteroid_saku.

Is there a better way?

Aside from testing the model and attempting to predict the sixth great surge, a question that arose from reading this book is: is there is a better way to acheive technological progress?

That is, do we need a boom-bust cycle, driven to regular disaster by uncontrollable financial forces?

What’s the alternative? Communism certainly achieved the first successful space program, but it collapsed completely, after decades of stagnation. China’s 21st century form of state capitalism might be able correct for some of the problems of this process, but that remains to be seen.

Another possibility is that technological progress and finance itself fuse. The Bitcoin whitepaper was published in 2008, right after the the 2008 financial crisis. It is both a technological phenomenon and a financial one. Currently all Bitcoin are worth about $1 Trillion, or 5% of U.S. GDP. If it becomes big enough, it’s possible that it will enable new forms of coordination that can correct for the problems of our current system.

One possible scenario (warning: speculative, not a prediction, and definitely not financial advice): bitcoin becomes the dominant global currency, and being a deflationary currency, it’s value will grow over time. Any and all investment in new technologies will have to compete with the default currency’s rate of return. It would also raise the standard for investments, so that investors’ due-diligence includes a “Proof of Efficacy” that is as rigorous as bitcoin’s Proof of Work. This higher-standard environment could have sigmoid (S-shaped) growth curves without crashes in the middle, since the technologies people are investing in can have direct input into smart contracts on the bitcoin blockchain. This would shorten the feedback loops between development of new technologies and actual economic performance, thus preventing situations where finance completely decouples from production and an unsustainable bubble forms.

I intentionally avoided talking about bitcoin and cryptocurrencies until the end because they are in a new category that is both new technology and financial entity. It’s possible that crypto will become a primary tool of financial capital, but not become a technological revolution in it’s own right. It’s also possible that all the cryptocurrencies will fail and be remembered as promising experiments whose long-term role was as a petri dish of ideas for how to improve finance. But I do think it is remotely possible that it could represent the final merger of information technology and finance itself, which might change the dynamics of future surges. Right now we don’t have enough information to know how they will fit in technological and financial history.

Conclusion

This book is a stimulating read, and I would recommend it to anyone who is interested is technology or finance. The primary idea is a 50 year cycle of S-curves driven by new breakthrough technologies, and co-evolving with finance and the regulatory state. All these things come together to create a predictable lifecycle of technological growth that transforms human society to a higher standard of living, creating new normals and seeding the next big surge.