Compound Growth 📈

There are some ideas that are obvious to a few mathematicians, scientists and economists, but which are not widely understood or appreciated. One of the big important ones is compound growth.

“Once you start thinking about growth, it’s hard to think about anything else.”

– Robert Lucas, Nobel prize-winning economist

Before launching into an explanation, I want to start with a question: “Would you rather be 1000 times richer today, or become 2% richer each day for a whole year?”

One way to solve this is to find out what 2% growth adds up to after a year has passed. Each day you multiply your starting wealth by 1.02 to make it 2% larger, so after 365 days, you can multiply all of them together and write it in exponent form:

$$(1.02)^{365} = 1377.40$$

Even though it takes a year, and 2% seems small, the end result is being 1,377 times richer, instead of only 1,000, the downside is that it takes patience.

The act of multiplying that 1.02 each time compounds the growth, and each compounding raises the exponent, so another term for this is exponential growth. Here is the exponential curve 1.02x for x between 1 and 300:

Let’s plot this 1.02x curve on a logarithmic chart to see what exponential growth looks like in logspace:

Straight line with a slope of 2, this generalizes too, so 1.05x has a slope of 5 in logspace, etc.

Thinking exponentially turns out be pretty easy, once you transform your curve into logspace, you can work linearly, and then transform back to get the right answer. For example, how long does it take 1.02xto double? That is, if you are getting 2% richer each day, how many days does it take to double your wealth?

Doubling period

TL;DR: Take N% and divide 70 / N. That’s how to find the doubling period.

If you are curious why this works, read on, or feel free to skip past this section if you don’t care. There’s a point to all this math.

To find the doubling period for our growth rate g (in the example above, g = 0.02 for 2%), we want to know the number of steps it takes to turn 1 into 2, so we can set up this equation:

$$2 = (1 + g)^t$$

Then take the natural logarithm of both sides:

$$\ln(2) = \ln((1 + g)^t)$$

Then apply the log rules to simplify:

$$\ln((1 + g)^t) = t\ln(1 + g)$$

Solving for t:

$$t = \frac{\ln{2}}{\ln{(1+g)}} = \frac{.693}{\ln(1 + g)}$$

Then notice that ln(1+g) ≈ g, and we usually say “2%” instead of 0.02, so multiply both parts of the fraction by 100:

$$t \approx \frac{69.3}{g} \approx \frac{70}{g}$$

So, armed with this simple trick, if you read “The GDP of China grew by only 5% last year!”, then you know that, if that was sustained for 70/5 = 14 years, China’s economy would be twice as large by then. Or, if the population is growing at 1.4% per year, and that was sustained for 70/1.4 = 50 years, then the world population would double to around 15 billion.

That trick will be useful to you when thinking about a mortgage, the economy, the population, or anything that has a consistent N% growth or decay, sustained over some number of years.

The word “sustained” is doing a lot of work

Now to the real world, can anything grow at a constant N% forever? The Club of Rome, a group of heads of state, think no. They released a report in 1972 called Limits to Growth, but their models assumed a fixed, finite set of resources, and then went on to show that those resources would eventually be depleted. That follows logically from their assumptions, but those assumptions are wrong.

Take garbage, landfills are useless right? Well, at our current level of technological development, yes. But it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to think about robots that can mine landfills and re-use those materials, it might take 100 years, but there’s no reason to assume those materials are going to be useless forever.

What about fuel? Fossil fuels do get used up, and on their own, take millions of years to feed plants, decompose, and form hydrocarbon deposits for use again. But it’s already possible to suck CO2 out of the air and turn it back into fuel, Prometheus Fuels is doing it now, they claim to be able to do it in a cost-competitive way, we’ll see. But it’s possible, and probably the long-term solution to making air travel sustainable.

Also, oil wells and shale formations will get harder and harder to extract, raising the cost of producing oil, which will make electric cars cheaper by comparison.

When resource a gets scarce, the price rises, which humans respond to by consuming less of it. If the price of a resource rises enough, people start looking for alternatives. This takes pressure off the scarce resource, which then prevents the price from rising further. This responsiveness of price to scarcity, and of humans to price, is what economists study, and it’s a necessary part of trying to understand economic growth and resource consumption.

This is also why a carbon tax would be so effective at reducing CO2 emissions. It would make gasoline and natural gas more expensive, which would make electric cars and electric heat pumps more attractive by comparison, and then people would switch on their own, for reasons of thrift.

So resources are only finite in the short term. Also, the resources humans care about change over time, so a fixed, finite pool of resources is not the right way to think about the long term.

Also, I haven’t even touched on asteroid mining, but that’s an elephant in the room in all these discussions. When a resource becomes abundant, it’s price drops. Aluminum is a good example, about 200 years ago, aluminum was used for fancy forks and coins, it was expensive because it was scarce. But a new discovery, of using an electrolytic process to separate it from bauxite ore, turned it into an abundant resource that we use to wrap leftover food and throw into the trash.

Gold burrito foil 🌯

Gold is another potential future example, for the last 4000 years, it’s been a good store of value, because it’s very hard to mine, and it doesn’t rust or tarnish. However, big gold deposits exist in asteroids. Recently some trashy newspapers published the headline “GOLD ASTEROID WILL WIPE OUT THE GLOBAL ECONOMY”, which is bogus. It would have a big effect, it would wipe out the value of existing gold deposits, but we have been off the gold standard since 1971. The world economy produces around $70 trillion each year, the value of all gold currently mined is about $7.5 trillion. That means a 10% dip in the world economy for just one year, but then you also have to look at the boost it would give to the electronics industry, and the burgeoning gold foil industry, which would be awesome, admit it.

Back to sustained growth, let’s look at Old Faithful, the U.S. economy.

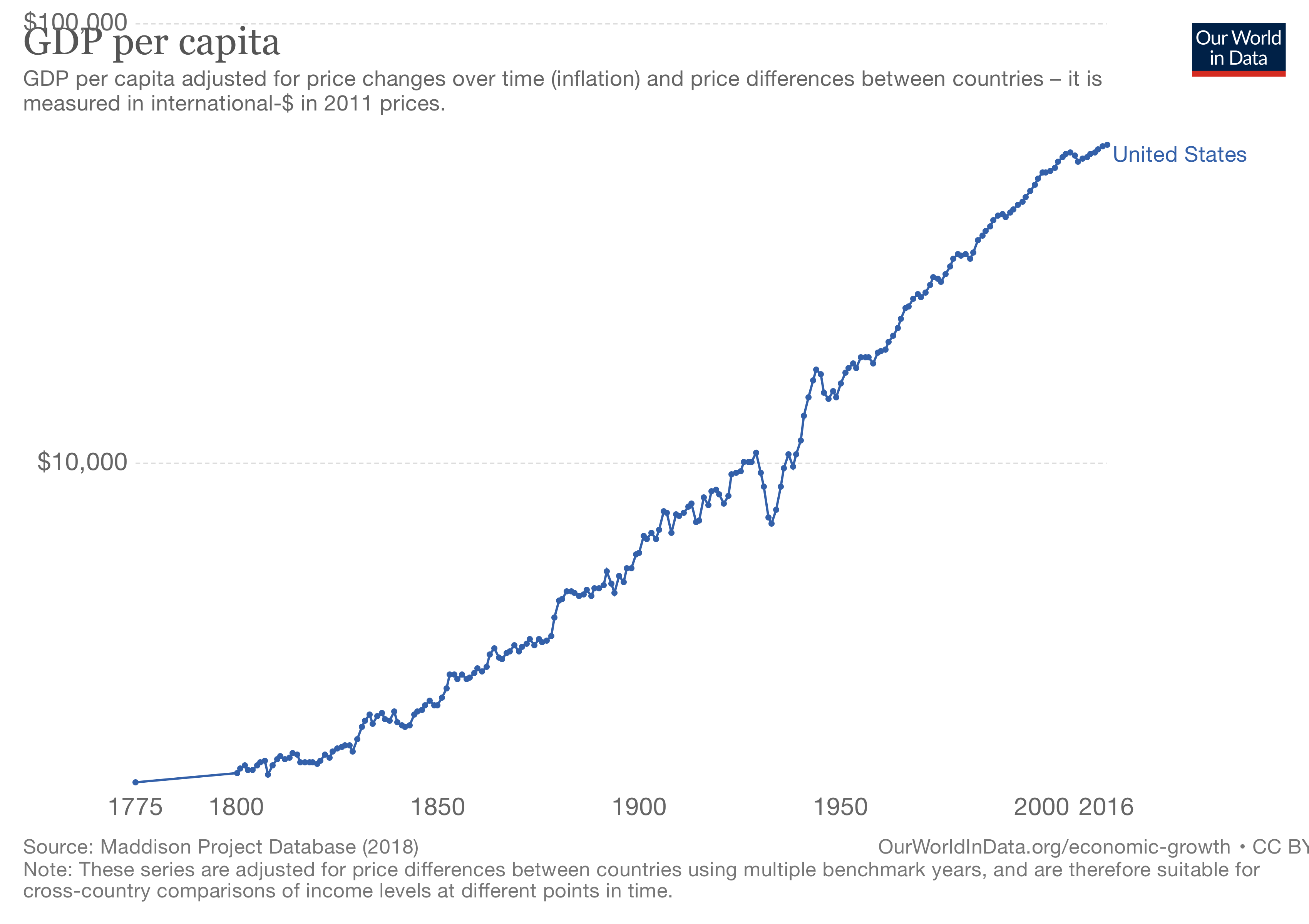

The unrelenting consistency of the economy of the United States

We define “the economy” as GDP per capita. This is an approximation of how much the average person produces, in dollar values. Looking at the last 240 years in the U.S., in logspace, we see what looks like a straight line, with a little fluctuation around 1930-1940. That’s what the Great Depression and the subsequent recovery look like from a zoomed-out perspective.

So the U.S. GDP per capita in 1800 was about $2,000 per person (in 2009 dollars), and in 2013 it was about $50,000 per person, also in 2009 dollars. That is a 25x multiple. Now, this averages over a lot of people. The workers in the industrializing north and Midwest are earning actual money, while slaves in the south are not being paid at all, the slave owners are making a boatload of money without doing anything, and the financiers in New York are making a lot more than the workers, partly from wise investment, and partly from gambling and corruption. Overall, the per-capita view hides a lot of this variation. That said, in practice, GDP per capita is such a good predictor of so many things we associate with progress, that it’s worth studying.

Notice that the civil war and the abolition of slavery (1860-1865) don’t even register on that GDP per capita line.

Why would such a seismic event in U.S. history seem so unimportant to the economy? It’s because slavery only benefited a tiny cabal in the south, and overall contributed next to nothing to the prosperity of most Americans. It could and should have been abolished at independence, and it’s a shame that it lingered on for another century.

Population considerations

The GDP-per-capita measure divides GDP by the population, so it can theoretically rise with a falling population. It can also rise with a static population, and it can rise with a growing population.

Let’s take a small detour on the topic of population, since it is another kind of growth that is both misunderstood and turned into an object of fear.

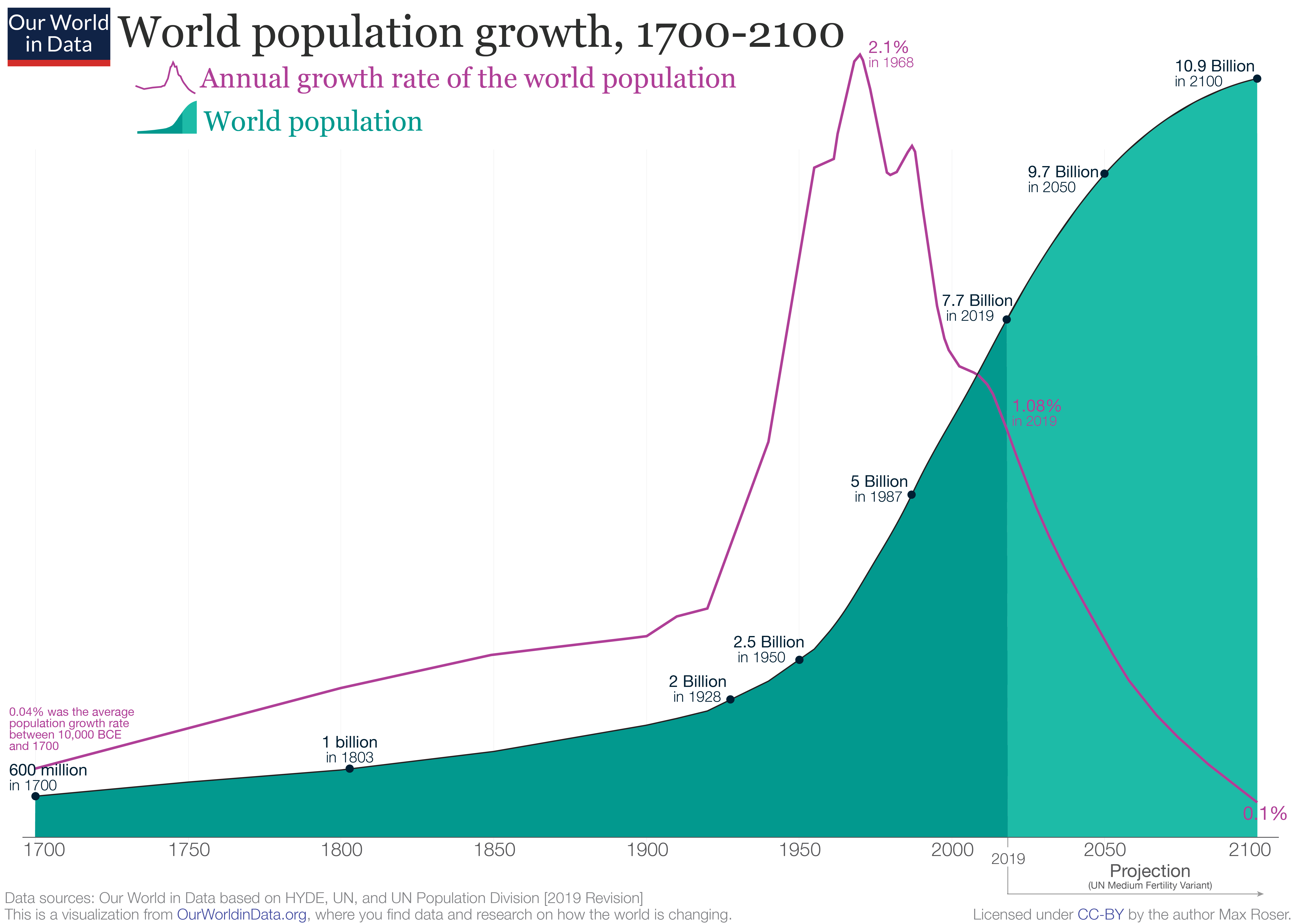

Here’s the last 300 years of population, and the growth curve superimposed on it:

From 1700 to the early 1900s, the growth rate is growing, so it’s faster than exponential. Then, Fritz Haber discovers a process for extracting nitrogen from the air, and suddenly nitrogen fertilizer became abundant, which drove down the price of bat guano, which destroyed the incentive to mine guano in Peru. Food production accelerated, which meant far more people could be born and fed. That vertical spike in the middle coincides with the Baby Boom, and that was made possible by cheap food and fertilizer.

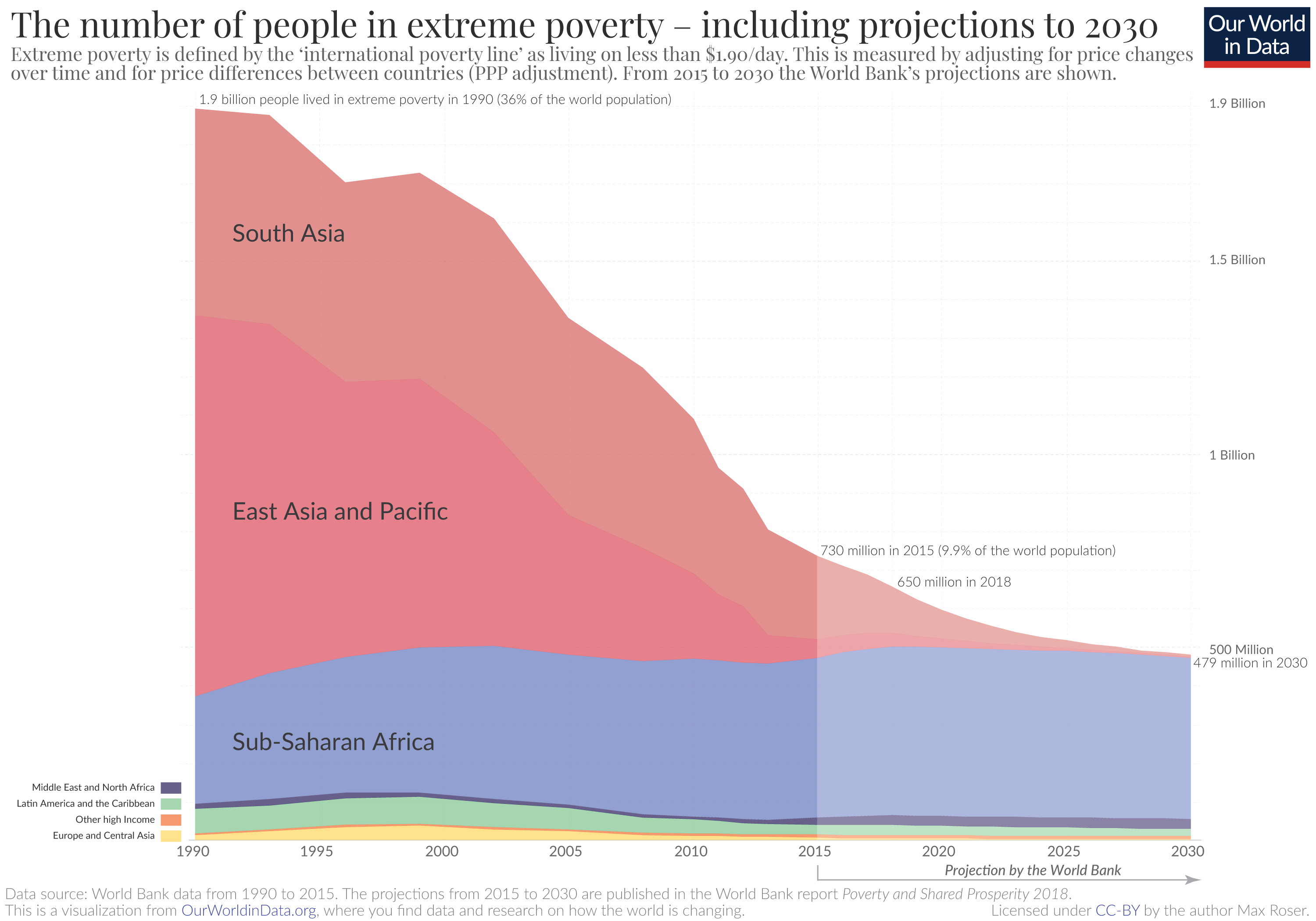

Contrary the worries of Thomas Malthus, population growth did not lead to famine and poverty, it actually lead to one of the fastest periods of economic growth in the rich world from 1945-1975. That is what French economists call Les Trente Glorieuses (the 30 glorious years from 1945-1975). Around the time that period ended, the Club of Rome was back echoing Malthus. It didn’t stop there though, since 1990, as globalization has advanced, and the rest of the world got access to global markets, extreme poverty has dramatically fell:

Economic growth is not hindered by population growth, it’s actually helped by population growth. In a very real sense, the more the merrier.

But can the population grow forever?

This question is a bit easier to think about, since human bodies haven’t changed in size very much, and when we think about the next 10,000 years, we shouldn’t expect large morphological changes in human evolution. Because both human bodies and the Earth can be assumed to have a fixed size (sorry Expanding Earthers), there’s a limit to the population on Earth. Even then, we haven’t begun to fill out the space we’ve carved out for the U.S. in 2020. There are 330 million Americans, with 93 per square mile. The European Union has about 500 million people, with 287 per square mile. China currently has 1.4 billion people, with 389 per square mile. India has 1.34 billion people, with 1,167 people per square mile.

This means that population of the area the U.S. controls could grow more than 10x to 4.34 billion people by going to India-level density. And by that point, new materials that enable taller skyscrapers and subterranean infrastructure could make that level of density far more luxurious than life in India today. Economic growth means richer people, with longer lifespans, better entertainment, more effective tools, more leisure time, and a larger frontier of things they know to be possible. This is why thinking only on the Earth is a failure of imagination. Humans can, and should, grow outwards into space.

The next 200 years: a scenario

Suppose the global population grows at 1.1% per year for the next 200 years. Since 70/1.1 = 63.6, it doubles every 63 and a half years. After 200 years, the world population doubles three times to hit 60 billion humans. Also assume that Old Faithful, or the average 2% U.S. GDP per capita growth continues for the next 200 years.

(These assumptions are for entertainment purposes only and should not be interpreted as predictions or investment advice)

By 2220, there are 60 billion humans on Earth. The earth finally feels too crowded for new humans to be comfortable there. But after centuries of sustained economic growth, American’s GDP per capita is around $3,120,000 (in 2020 dollars, adjusted for inflation). This means that the average American is a millionaire, there are trillionaires, two quadrillionaires, and some guy who bought bitcoin in 2040 and held onto it, and somehow hasn’t died yet.

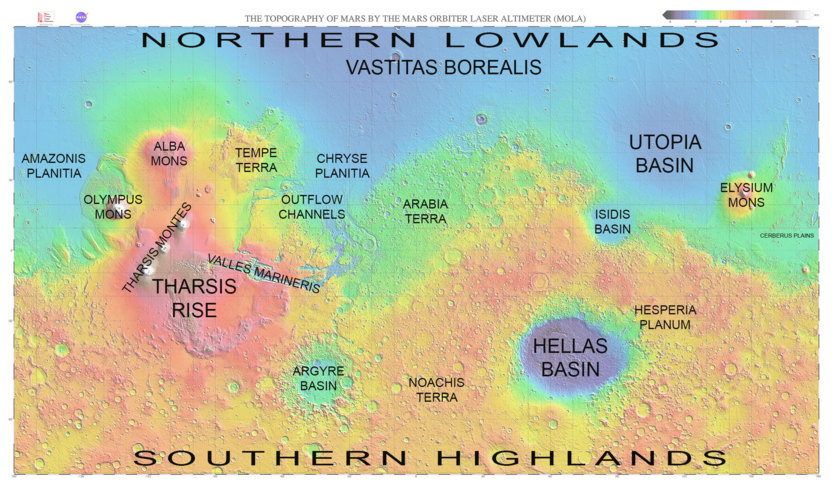

The SpaceX Mars colonies grew rapidly toward the end of the 21st century, and finally hit a self-sustaining population in the early 22nd century. Elon Musk was buried at the summit of Olympus Mons on Mars, August 17, 2081, at age 110.

The Martian colonies kept developing throughout the 22nd century, and by 2200, were an indispensable part of the asteroid mining industry.

At the dawn of the 2220s, with a crowded Earth, and a sustainable outpost of civilization on Mars, the new frontier opens, and the new exodus begins. The weird irony of real estate costing less on Mars than it does on Earth is not lost on anyone. The U.S. government declares Chryse Planitia the 89th state:

The Chryse Planitian state economy specializes in water extraction from the Martian regolith. They export water to the other colonies for much less than the SpaceX corporatocracies have been charging.

Most of the Martian economy is oriented around supplying the asteroid miners. The asteroid miners use Martian fuel, materials, and skilled labor, while exporting raw materials and manufactured goods down to Earth, the richest of all human settlements.

This is only the beginning. At 60 billion humans in the solar system, and the new multi-planetary reality settling in, humans start to plan out scenarios for 2300 based on the old vision of 1 Trillion Humans that Jeff Bezos talked about in 2020.

A trillion?! How will we fit that many people on Earth, or even Mars, which is smaller?!

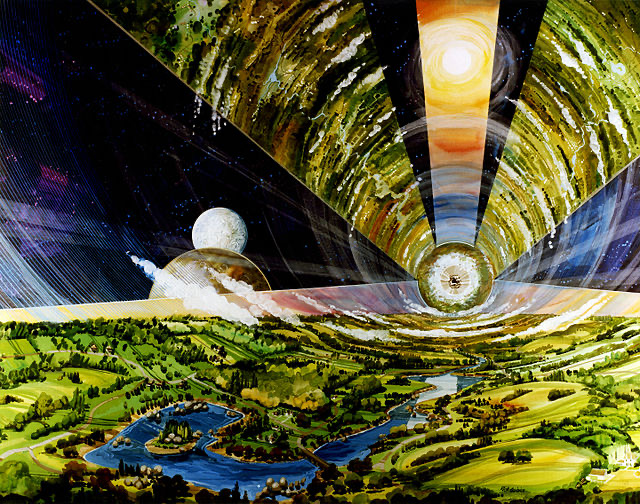

O’Neill cylinders. When Bezos was a student at Princeton on Earth in 1980s, he learned about Gerard O’Neill’s idea of a new frontier of cylindrical colonies that spun, and used centrifugal force to enable artificial gravity.

So the inner solar system is filling up, humans live more than 100 years, there are more than a trillion people, and everyone lives like millionaires. Growth is done right? The solar system is big, but still finite!

There is always room to grow, with closed-loop O’Neill cylinders launched into interstellar space, the limit is only the speed of light.

But the galaxy is finite!

Intergalactic travel.

The local group of galaxies is finite!

Inter-galactic-group travel

The universe is finite!

Well, maybe, that’s an open question in cosmology, but let’s assume it is.

If we live in a finite universe without boundaries, which is also expanding, we can probably create new baby universes with black holes. Even if we can’t, then remember that the universe is expanding, so we can keep growing our population and universal economy as long as the universe keeps expanding and we can harvest enough energy. After the stars burn out, our descendants will have to get creative and harvest rotational energy from spinning black holes. For a really long term view of the universe, watch this Timelapse of the Future by MelodySheep.

All this is to say that economic and population growth are only limited by cosmological growth and available energy. The cosmos is expanding faster than the speed of light, so that’s not a realistic barrier to growth.

Growth rates

We have learned how to think about exponential curves in terms of their doubling rates, and how to quickly calculate how much larger something would be if that rate held steady. We have dispelled the harmful Malthusian scares about overpopulation, and argued against the “Limits to Growth” view. It’s worth revisiting that math to see what kind of difference another 1% can make.

Suppose the economy averaged 1% growth per year, for the next 70 years, how much does it grow? It doubles. Now assume it grows 2% per year for the next 70 years, how much does it grow? It quadruples. Finally, assume it grows 3% per year for the next 70 years, then it would octuple, or grow by a factor of eight. Each additional 1% seems small in a single year, but adds up to another order of magnitude after 70 years. This is why each little bit of growth matters. You can literally make your great-grandkids twice as rich by boosting annual growth by 1% per year.

Conclusion

Compound growth, whether it’s interest on a savings account, or a population, or an economy, has a simple mathematical form, which can clarify our thinking about the future.

In addition to being easy to think about, it’s also an indispensable part of the story of human freedom. Humans become more free when they are richer and have access to more sophisticated tools. This is another way of saying growth can make everyone better off.