Dunbar's number, Random Graphs and Sapiens

Why is human society so flexible? In 1000 years, we have had the Great Schism of 1054, the Norman Invasion of 1066, the Magna Carta (1215), the Mongol Empire, the Ming Dynasty in China, the Portuguese and Spanish maritime empires, the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and the creation of the idea of “Sovereign Nation-States”, the Dutch Empire, the British Empire and the creation of joint-stock companies. The Reformation led to new religions. All those protestant sects that broke away from the Catholic church had the effect of sparking a revolution in literacy and commerce. The spread of printing also lead to a revolution in science. The American and French revolutions (1780s) lead to the creation of republics with freedom of religion, and freedom of speech. The Ottoman empire (1840s-1920) united many different Islamic territories into a single polity. The Russian revolution (1917) experimented with a radically different idea and created an empire that was the first to achieve spaceflight, and lasted almost a century. The Americans did SpaceX and Tiger King.

No other species had this interesting of a 1000-year run, and that begs the question: what is so different about humans that history is not the same as evolutionary history?

The historian Yuval Noah Harari argues that humans are unique because of their ability to flexibly work together in large numbers. The psychologist Robin Dunbar found the limit for the number of unique relationships humans can keep in their memory. It’s about 150.

Harari argues that humans can flexibly work together in large numbers because of our ability to use “fictive language”, or speak about things that don’t exist. As examples of fictional entities that large numbers of humans can coordinate around, he talks about gods, money, corporations, and nations.

These are things most humans treat as important, but which don’t exist outside of human brains. It’s true that there are real, physical artifacts built in service of these fictions, but they only have meaning to humans who believe in those things.

To a modern day tourist, the Pyramids in Cairo are just really big, neat stacks of rocks. But to an Egyptian living under the Pharaoh, they symbolized the ultimate authority and glory.

Think about paper $100 bills. The material they are printed on is almost identical to the material a $1 bill is printed on. The big difference is that almost all humans treat one as a hundred times more valuable than the other.

Humans can trust in those fictional things and work around the limitations of Dunbar’s number. Instead of maintaining millions of individual relationships with all the people involved in maintaining an empire, each person can trust in their neighbors, their local lord, the lord’s governor, and the emperor, and finally, a god or gods above that. This can neatly fit within 150, and leave space for new relationships. This also forms a hierarchical structure, a form which appears again and again throughout history.

I am not saying it’s good, I’m saying it solves a problem. The problem is that large, coordinated groups of people are better at defending themselves, providing for their people, and surviving than small, uncoordinated bands of people. Teamwork at scale is unstoppable.

I want to explore the intersection of two ideas in this essay, using a mathematical tool called random graphs.

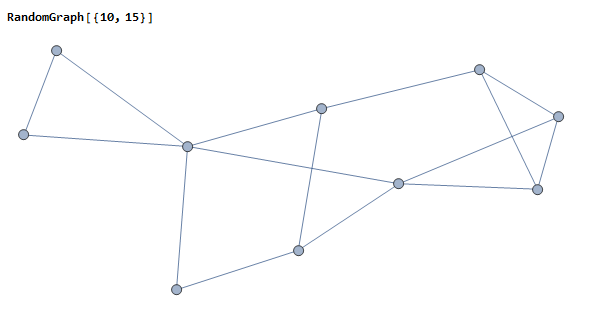

A graph is an object made of smaller objects, called vertices. Each vertex can link to other vertices through “edges”. Here’s a random graph with 10 vertices and 15 edges:

Since each human relationship is time-consuming to maintain, there is a natural pressure keeping the number of relationships per-person small. But, since larger groups of coordinated actors (citizens, believers, currency users) tend to do better economically and militarily, that means that surviving groups of humans will be among the largest.

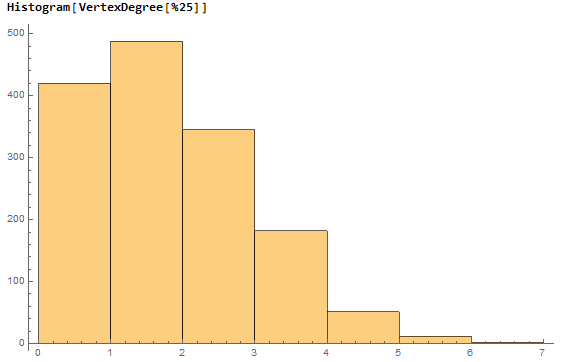

These opposing forces can be formulated in the language of graph theory: a vertex’s edge count should be small, but the number of vertices in a connected component should be as large as possible.

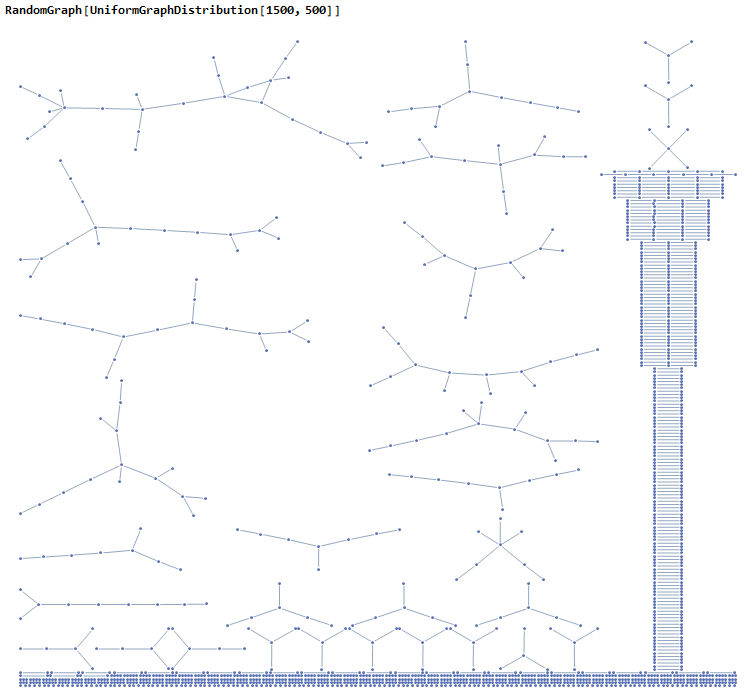

As an experiment, let’s take 1500 people, and look at the graphs that appear with only 500 total relationships.

This forms a lot of small hierarchical groups, where the most connected is the chief, or the king, or whatever you call it, and a lot of isolated “dust” of individuals who are totally alone.

In this scenario, the bigger clusters of people could absorb the individuals, and the clusters could fight among each other for land and scarce resources. Or, they could form alliances around trade or marriage, and use their larger size to beat all their common competitors.

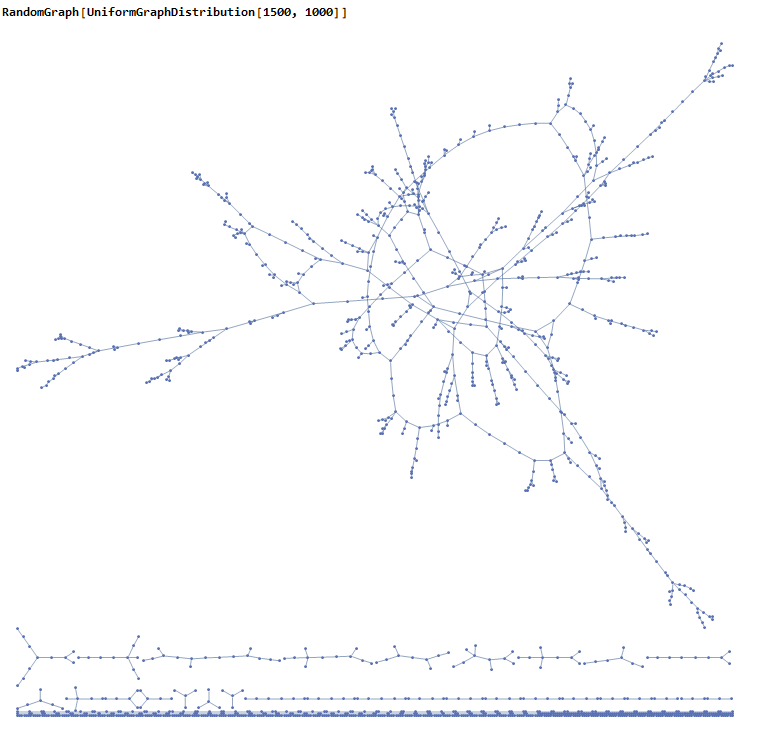

Assume time passes, and trade alliances form, royal families merge, defectors and revolutionaries break away but the trend is generally toward consolidation. Take the same population of around 1500 and double the number of relationships. Suppose this happens because the trade networks enable positive-sum growth, people get more nutrition, and venture out, trading with their former enemies. The economy grows, and the healthier, richer population begins forming new relationships.

I ran a few simulations, in all of them, they have one giant cluster, I call it The Empire. It completely dominates in terms of size, connectivity, and still has the nice property of most people only needing at most 4 or 5 close relationships:

Flexibility comes from this low average vertex count. Why? If you only have to convince 4 or 5 of your most trusted relationships to defect, you can break an Empire in half and have a good chance at ruling and defending it.

Although, if you start introducing breaks into the graph, you need something to hold it together so it doesn’t fragment back down to where we started. Belief is the special sauce that keeps clusters coherent after a break in the graph occurs.

Starting with my first example: The Great Schism of 1054, the Christian church had survived from 330 AD to 1054 AD, but it split into the Western Roman Catholic church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. The two halves remained coherent and exist to this day, and it’s because the members still believe, it’s just at one side changed the parameters of belief ever so slightly, and the clusters stayed internally coherent, even as they competed for believers and continued to evolve and expand.

The other, more familiar example is the British Empire and the United States of America. The Yanks wrote down a constitution that was very similar to the British constitution (which, weirdly, was never written down). The similarity of the two systems helped to get buy-in from other fellow defectors, so that when the British empire broke in two, the two would quickly become equals, and then the new empire would eventually dominate.

In conclusion, I think belief is very important, whether it’s belief in a faith, or in a constitution, or in the value of a currency. The Dunbar number is not really a limit if you have the right structure, held together with something as potent as humans believing in the same thing.